|

|

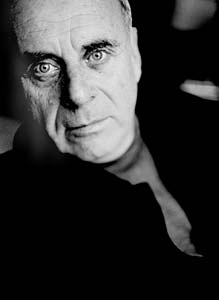

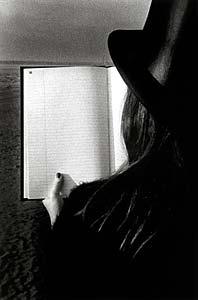

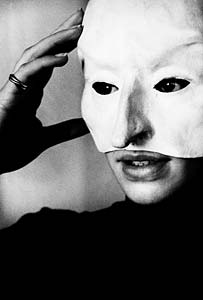

Ralph Gibson |

||

|

||

| Chris/Larry: Let us begin with a

question about your vision. Your work has an extraordinary balance in it,

a certain kind of energy to it. Can you tell us about your state of mind

when you are shooting? Ralph: Well, for the longest time I have known that photography for me is not directly linked to an external event. For example if I say that tomorrow thereís going to be an execution at 12 oíclock. You get there, we can all win a Pulitzer prize. If you get there at 12:01 you miss your shot, as it were. So, what I wanted to do, is be able to make my perception of anything become the subject itself. And for this reason Iíve attempted to take pictures of simple things, you know, like a cardboard box, or a chair, or a spoon. Very humble objects. Iím not terribly drawn towards the epic event. Iíd like to make something totally insignificant into an object of importance, by virtue of how photography works. Chris/Larry: How much of your shooting is actually planned? How much is spontaneous? How much do you pre-conceptualize what youíre going to get versus just working with the subject and the light and just responding to it?

Ralph: I know an image when I see it, but I never know what my next photograph is really going to be, necessarily, unless Iím working on a project. I have several projects currently under way. Iím working on Berlin at night on a thing called ďI am the NightĒ. Iím also working on a project for Gibson Guitars entitled ďLight StringsĒ with my friend the guitarist Andy Summers. This will be a book and a traveling exhibition. So, in a case of something like that I know what the subject matter will be. Or when Iím doing nudes for example, I know that tomorrow at 3:00 a model is coming to the studio. However, Iíve recently been invited by the Mayor of Strasbourg in Alsace to come this fall to make twenty photographs of the area. This will mean that Iíll be entirely at large, as they say. Iíll just be drifting around and I will respond to what I think and feel, and one picture will inform my next one, and I will follow the tone. The same thing as when I lay out a book. I make a couple of double page spreads that seem to have a certain kind of emotional tone, which I then follow in subsequent spreads. Chris/Larry: When youíre walking around shooting, say, twenty pictures of an area, what kind of equipment do you bring with you? What is the technology you use to capture your images? Ralph: Itís very simple. I carry two Leica Mís. I have two M6ís and I usually take three lenses. A 35, 50, and 90. And one body has color, one body has black and white. I might take a 135 in the case of Alsace because theyíll probably be some landscapes and Iíll want to flatten them. So I will use the long lens. But I really believe that the problem for me is for me to perceive something clearly, and it doesnít matter where I am. Iíve been in Japan, Iíve been all over the world and I come back with the same photographs (laughs). It appears that wherever I go I tend to bring my vision with me. Chris/Larry: You do capture an energy that is unique to the area. Like in your pictures in Japan, there was a certain energy that came through those, which I thought was a bit different, than in your European work. Ralph: When I think of energy I think more in terms of composition, a certain tension on the surface of the image. Iím very much the formalist in photography. Iíll take a picture of anything in an attempt to compose it within the proportions of the golden means (the 24x36mm proportion) just to see if I can compose it perfectly. And I think that the energy to which you refer to has more to do with these issues. Chris/Larry: When you use Leica rangefinders, is there a different type of visualization because the way the cameraís viewfinder is designed? When you shoot do you crop at all, or is it all in that frame?

Ralph: I have spent forty years working with the Leica rangefinder. The rangefinder enables one to see whatís outside of the frame as well as whatís inside of the frame. You make a decision predicated on the presence and/or the absence of various aspects of the subject. With a reflex, the camera determines what is seen, and half the time it's out of focus. One could follow a reflex around the world and focus it from time to time until it came across a picture. With a rangefinder you see something, you make the exposure and you continue to look at what youíre seeing. The rangefinder is ideally matched to the perceptive act, the personal act of perception. I only use a reflex for extreme close-ups. Chris/Larry: You have a very tight, formal kind of design to your work. Do you ever use a tripod? Ralph: I rarely use a tripod, unless Iím in the studio with a long lens shooting a nude with a long exposure. I rarely use a tripod and I rarely crop. And even if I did, I wouldnít admit it (laughs). Chris/Larry: Well, when youíre actually shooting, do you go through a lot of film, or are you very conservative in the way in which you make your exposures? Ralph: I donít bracket, if thatís what you mean. Iíve discovered that when I was shooting Kodachrome or something that Iíd have to bracket because of the extremely short latitude of material. But now, with these very sophisticated color negative materials, they are much more forgiving. Thereís a meter inside the Leica. I use it in the broadest most general sense of the word. I usually center weight it and I put it on whatever color I consider to be the most important part of the subject in the photograph. In black and white I hardly pay any attention to it at all. Chris/Larry: I was thinking of the dynamic of working with the subject. You work with shadows in an incredibly dynamic way. Shadows are very critical to the power of your pieces. Do you play with the shadow by movement and changingÖ. Ralph: For example if youíre going to make a drawing, you take a paper and a pencil and add lines, add marks, until you finish your drawing. It's additive. When I make a photograph, I move in closer and I take things away, and I take things away, until I get everything out of the frame except what I want. Therefore my process is considered subtractive. Now part of this subtraction has to do with casting things into deep shadow. I eliminate a lot of unwanted material, activity into the shadow area. And in so doing, create a shape. Instead of just being a variation on light, for me shadows become cut forms, they become shapes. And I discovered this by photographing primarily in bright sun and exposing for highlights, which is pretty easy to do. Most people struggle to get detail into their shadows. I was never interested in that kind of photographic expression particularly. Chris/Larry: Your work really takes advantage of the 35mm film dynamic range, with its characteristic graininess and tonality. How has the changing of materials, the newer films with finer grain, effected you? Have you pretty much stayed with the one film and developer combination?

Ralph: Iíve used Rodinal since 1961. I use Tri-x almost exclusively but occasionally, sometimes I get in the mood to use Fuji 400. But either one is the same to me. And for my night work, Iíve been very happily working with Fuji Neopan 1600. But theyíre all souped in Rodinal. I develop all my own film myself, personally. And I also base the fact that I develop my film personally means that thereís going to be certain irregularities in my agitation. And I have discovered that, in these irregularities there is some creative input. I donít want my film to be developed too well, too cleanly, too smoothly. I donít want that slick look. Iíve had a life long relationship with grain. You know I originally started out as a photojournalist when I was young. Iíve always felt that grain gave texture both to cinema, as well as photography. Iíve used it for any number of reasons for the entire length of my career. Itís almost harder to get a grainy image nowadays than it is to get the shot. Chris/Larry: I guess that was part of my question. I know how much materials are changing for all of us. What about your color materials? Ralph: I use Fuji Superia 100. Itís 100 speed negative film Chris/Larry: And have you experimented at all with digital cameras?

Ralph: I have I have a wonderful relationship with Leica and they send me things to experiment with. Iíve used the large S1, that big studio camera, and Iíve used the little Digilux. I have four Macintosh computers in my studio as we speak right now. Digital photography is about another kind of information. Digital photography seems to excel in all those areas that Iím not interested in. Iím interested in the alchemy of light on film and chemistry and silver. When Iím taking a photograph I imagine the light rays passing through my lens and penetrating the emulsion of my film. And when Iím developing my film I imagine the emulsion swelling and softening and the little particles of silver tarnishing. Chris/Larry: So youíre not just previsualizing the image, youíre visualizing the process? Ralph: Iím communicating with my materials. Itís different than previsualizing. If you talk to a sculptor about how he looks at his rock or wood, you realize that he has a special relationship to his materials. In music itís called attack. A concert violinist once told me that if Rubinstein came in and hit concert A, it would sound different than if Horiwitz came in and hit the same note. And a good musician will recognize which one was playing based on the performerís attack. When you look at de Kooningís brush stroke you can see the energy of the bristles of the brush right in the stroke of the paint. This is another example of attack. So Iíve applied some of these principals to my relationship to my materials and I think of them with great respect. I think film has more intelligence than I have. I could not make a roll of film. I learned this when I was an assistant to Dorothea Lange, this incredible respect for materials, almost homage. But anyway, the big emphasis in digital photography is how many more million pixels this new model has than the competitorís model. Itís about resolution, resolution, resolution, as though that were going to provide us with a picture that harbored more content, more emotional power. Well in fact. Itís very good for a certain kind of graphic thing in color but I donít necessarily do that kind of photograph. So when it comes to digital, I have to say that digital just doesnít look the way photography looks, it looks like digital. However, I strongly suspect some kid is going to come along with a Photoshop filter called Tri-X, and you just load that, and youíve got your self something that looks like Photography (laughs). Itís about the same relationship that videotape has to cinema. Digital imaging and photography share similar symbiosis. I think itís a mutual coexistence situation. I donít think they even compare. Chris/Larry: Well, you have been known for your skill in the darkroom and for that whole energy that you sense with your film and your process and your printing. How does working with Photoshop enter into that? Does the possibilities of the digital darkroom affect what you can produce and create visually?

Ralph: Photoshop is a magnificent, magnificent experience. I have a laptop at home and I learn new moves every night. While surfing I seek out Photoshop tutorials. I did all the scans for the book, ďDeus ex MachinaĒ, and I did all the duotones and color seps in CMYK, everything. Photoshop enabled me to create and set inking levels that remained consistent throughout the entire book. The first page had the same density as page 768. For me, Photoshop is about unifying my body of work for either output to lithography or Iris prints. Now I want to introduce another idea here. I believe that the computer has evolved technology that has accelerated and enhanced the quality of the emulsions of our black and white and color films. You canít really separate computer technology from the fact that weíve got ASA 3200 going on now. However the same computer that has made this nirvana of great photographic films, has eliminated the paper, the substrate upon which we are to print them. Thereís nothing to print on now. You can either print on Ilford, and if it doesnít look good on Ilford, then you can go ahead and print it on Ilford (laughs). You know how important the darkroom look is for me, and I donít have those emulsions that feel like theyíre a quarter of an inch thick any more. If you catch my drift. Chris/Larry: And yet youíre not tempted to go digital? You mentioned youíre doing Iris prints. We have seen many folks working with the Epson printers, printing on a wide range of art papers that they never would have had access to before. Ralph: I have two Epson 3000ís and a 1200 and a 780. I have four Epson printers here. Iím fully into the Epson, but I use them for making my dummies. Chris/Larry: Have you tried printing with the quad tone inks, like the ones from MIS (www.InkSupply.com).

Ralph: I have. And Iíve gone to InkjetMall.com (Cone Editions). Iím pretty much abreast of whatís going on. And I have used those inks, and theyíre great. Itís just that theyíre not better or worse than photographs. They coexist. Theyíre not photographs. Theyíre another kind of very beautiful print. Chris/Larry: A lot of people would have said, years ago, that offset lithography was not capable of being a true art medium. But you, with your books, have done a beautiful presentation of your photographic work. So, youíve taken something that perhaps was never originally intended to do wonderful dynamic artwork and through your understanding of the inks and the papers, you were able to create thirty outstanding books so far. Do you think that other photographers and perhaps yourself are going to continue to play with inkjet prints until they also reach new levels? Ralph: Oh sure, I mean, weíre watching an exponential rate of research. Something that was cutting edge last year is obsolete. You get those catalogs and then you look at the Internet and see whatís going on. Itís a wonderful time to be involved in imaging systems now.

Chris/Larry: I imagine youíve been laying out books on computers for quite a few years now. Ralph: About ten or fifteen, yeah. Chris/Larry: Now thatís about as long as desktop computers have been around. Ralph: I got in very early. It takes that long to learn Quark and Photoshop (laughs). Chris/Larry: And you still donít have it all down, right? Ralph: Iíve got an endless number of colleagues who call, you know how you call for tips on how I do this and how do I do that. And I tell them itís on a need to know basis. Sometimes, the only things I know how to do in Photoshop and Quark are the things I need to do for my work. You know, you never learn the whole program. Chris/Larry: How is producing a book substantially different then from creating prints for an exhibition?

Ralph: Well, for example, I have a show up right now at the Creative Center for Photography in Arizona, of my Iris prints from ďEx LibrisĒ. And that same show is going to open at Helsinki next week. Now, those prints are four feet, 48 inches by 35 and I have no control over the viewing distance in the gallery. So people will enter the gallery and look from across the room. Others will go up very close and examine the surface. Exhibitions basically show my relationship to photography, the making of my photographs. Books show how I think about my photographs. And in my sequencing and layout and scaling and such, one of the things Iím aware of is the fact that almost everybody, nearsighted or farsighted, is holding the book within a few inches of one another. We all hold the book at pretty much the same distance, given the slight latitude in our visions. So, this means that there are certain effects that are guaranteed to work in a book. Certain experiences that are guaranteed to produce visual experiences. Chris/Larry: And of course you have two opposing pages in a book so you can juxtapose images.

Ralph: Which I enjoy doing very much. Iíve continued to stay enamored of the book making process. Quite often, as recently as yesterday and probably again this afternoon, I will scan something in wet on my Epson 1640 XL because Iím excited to see it. Iíll make the print in the darkroom and then Iíll squeegee it the best I can, sometimes I put it between two pieces of Mylar but that gives me Newton rings. So what I try to do is get it down on the glass as quickly as possible, and then Iíll take it back out and wash it and dry it and clean the glass (laughs). Chris/Larry: Thatís great. So youíre actually in some ways capturing tonalities on a wet print that may not even be there when itís dry. Do you ever scan your negatives to work from? Ralph: I am one of those people who happens to believe that you get better results scanning from flat art, rather than negatives. You know the world is divided. There are those who think you can scan from black and white negatives and get good results. I donít happen to share that view. I have owned a Nikon CoolScan and I still have one, but the truth is, I donít get the results that I want. And I have spoken to other photographers who corroborate my views. I think that scanning film works better for news agencies. Chris/Larry: What about scanning transparencies? Ralph: Transparencies scan OK. I donít mind scanning a transparency like Kodachrome, but I just donít shoot Kodachrome anymore. Scanning black and white or color negatives donít give me the results that I want. Chris/Larry: When you take a print that youíve created, you have this understanding that itíll be seen in a book. Does it even go further back to when youíre shooting that picture? Do you think in terms of what might oppose it across the page? Ralph: I have certainly done that. I have certainly had that experience. But, thereís always the act of discovery in the studio. I have prints up on my wall at all times, recent work. And sometimes it takes my weeks to see a relationship between a picture from Morocco and a picture from Berlin.

Chris/Larry: I see. So living with your pictures and interacting with them on a daily basis, gives you more insight. Ralph: Absolutely. Iíve known for years that I have to look at my work through every facet of my personality before I can claim that Iíve looked at the picture. And I assure you that I do that before I release anything. Whatever is in that picture, I know about it before it goes out. This is not the working photojournalist who does forty rolls a day and never sees any of it. Chris/Larry: Do you learn from the reactions of others to your work as well, or are you completely self-contained in your vision? Ralph: Well, what Iíve learned is not to pay any attention (laughs). Itís very simple. I realized that I finally had my audience when I did ďSomnambulistĒ. When I was about thirty I realized that the only thing that recognition would do for you is give you energy to produce more. But you know, I am not working as a professional photographer and Iím not seeking the approval of the client. Iím a much more difficult client, more difficult art director on myself. And I like to think that I donít care what people think about my photographs. Of course, that takes a lot of discipline to maintain that. Whether or not I succeed at sustaining that feeling is another question. However, I do not consider myself in the business of communications. I donít have a message. Samuel Goldwin said Ďif you have a message, send a telegramí. Iím doing it for myself to make myself happy and to see how it works. And then Marcel Duchamp said that an artist has a responsibility to his or her work to get it out. And I get it out, and I make a living from it. Chris/Larry: Well your book ďDeus ex MachinaĒ is a wonderful collection of your lifeís work to date. Itís 768 pages, a phenomenal collection of images. Itís an unusual format for a book on fine art photography at about six by eight inches in size. Why did you choose that particular approach?

Ralph: Because itís a series. Itís a series and itís a size that enables the publisher to get the maximum number of pages out of a sheet of paper. Chris/Larry: So the actual use of materials went into the concept of the book. And that undoubtedly helped keep it very affordably priced at $29.95. Ralph: Well thatís the other thing. We sold 22,000 in the first year at that price. This book format is called a klotz, which means brick in German. The minute I saw the format, I wanted to do one. Chris/Larry: So the capability of the printing medium itself gave you the design. Ralph: Yes, in this size format there is no paper wasted. You know how press sheets are conformed, right? If we had have made the page size bigger it would have wound up chopping a six inch slice of unprinted paper off the bottom of the sheet. This is a wonderful formula, and again thanks to the computer, this book flew through the press. We had 64 pages up on each side of the sheet. And they were all were equally inked because the presses are computerized too. This is a golden age of publishing. It has never been easier to do a book. Chris/Larry: Your latest book, ďEx LibrisĒ, is an homage to the whole concept of books. But itís interesting that you chose images that were in a book that was an homage to a book and then made large Iris prints from them. Ralph: I love the Iris process a lot. They function in a totally different way. They make a powerful presence on the wall. The more I go in to the digital thing, the more I like it. In that I feel that the whole digital experience is like, if you told me I could lift 10,000 pounds with my right arm. Thatís sort of how the computer makes me feel. Chris/Larry: The computer also has another dimension to it, of course. That is the whole world wide web. And the ability to not only process information on your local desktop but then to put it out there to the world. And thatís given a lot of photographerís leverage to exhibit and to show their work. When you created your web site at www.RalphGibson.com, did you perceive that as another publishing medium?

Ralph: I have observed that it functions in many different ways. Some people send an e-mail, say they just love the design. Other times somebody will call up and ask for the rights to use a picture for a book cover or something. Photographs look pretty good on the monitor. Thereís a lot of brightness and presence. Iíve know for a long time, even from the early days when occasionally Iíd be on television and they would put some of my work on. Even in broadcast the pictures looked OK. So, I feel that the atmosphere, the creative space of cyberspace does have itís own nuance and I know the young web designer, the woman I worked with, Brooke Singer, was very much aware of the presence, the tactility of cyberspace. I know that she was relating to cyberspace as I relate to light on film. Chris/Larry: Do you see the medium of the web being a whole new creative kind of space to move into? Ralph: Sure. However I havenít wanted to, other than timid forays into HTML. Iím not personally going there because my quest is linked towards increasing my camera handling skills with the Leica. You see, thereís a certain number of things one can do and I still have a lot of pictures that I want to take. Getting the work out is not as much of a problem for me these days.

Chris/Larry: As it would be with a younger photographer whoís just creating at this point. Ralph: Exactly. Chris/Larry: You had mentioned that people could contact you and ask for rights. Is there any way that someone can purchase prints from you, through your web site or through other ways? Ralph: Yes, Iíve sold a few, but people generally find that theyíre too expensive. People can contact my studio with inquiries. Chris/Larry: And you sell both silver prints and Iris prints, and what is your price range? Ralph: My prints are in editions of between 10 and 25 and sell for between $2000 and $7000. Chris/Larry: Would you have any advice to photographers who are just starting out? From your experience and from what youíve seen, what might you say to photographers who are either beginning or pushing in new directions at this point?

Ralph: I had the incredible opportunity to apprentice to Dorothea Lange and Robert Frank. Although I learned a lot from both of them, one thing that rides above it all, they both told me, they stressed uniqueness. You really really have to be unique. You have to come up with your own visual signature. And itís not a question of style. Our unique way of perceiving our own personal reality which is inherent within all of us. And it takes a while to get that harmony with your camera. But thatís where photography really begins for me and for some of the photographers Iíve admired through my lifetime. For example, you donít have to look at the signature to tell that itís a Cartier Bresson, you can see it from across the parking lot. And it has to do with the way he puts the image together. And itís something thatís carefully thought out, researched at great personal expense. Otherwise photography is very simple. They have all these PHD cameras now. That means just push here dummy (laughs). So, anybody can take that kind of picture. Chris/Larry: Have you seen any new photographers come along in recent years that have that kind of personal vision?

Ralph: Well sure, absolutely. Thereís a lot of very strong workers in fine art photography right now. Chris/Larry: And pushing it both in the digital realm as well as in the traditional manner? Ralph: Well, you know. Some people are working in digital. I think a lot of people are making digital prints, thatís for sure. Its Bill Brandt that made it very clear. He said itís really the results that count. If I see some great digital photography done with the little Digilux Iíll be the first one to tell you I knew it could be done (laughs). |

||

|

All Images on this Page © Ralph Gibson |

|

All photos on this site are available for stock or

fine art sales |

| Slide scanning for ZAPP and other digital jury systems |

|

1970s ABA and NBA

Basketball photographs |

|

Web site content © Larry Berman |

email Larry Berman - larry@bermanart.com

|