Chris and Larry:: When did you begin

assembling your images from multiple negatives?

Jerry: It was the late 1950s. I did a little bit then and then

it really took hold once I went to Florida in 1960.

I had the benefits of studying with Henry Holmes Smith at Indiana

University. He had worked with Laszlo Moholy-Nagy in Chicago and was open

to all kinds of experimentation. He actually made photographs by

refracting light through syrup poured on glass.

Chris and Larry:: What led you to see the power in collage? At that

time, straight photography as done by Edward Weston or Ansel Adams was

considered the correct way to do photography.

Jerry: I had become restless with trying to find an image that

satisfied me in camera. The idea that the creative gesture in photography

was when you clicked the shutter was popular when I was a graduate

student. A lot of times I found that if I thought too much about the

image, Iíd talk myself out of shooting, or I ended up with a lot of images

that I thought were okay, but not quite good enough.

When I studied photography at RIT each darkroom had one enlarger. Then

when I started teaching we had a group darkroom. I was still using one

enlarger, which was labor intensive for multiple printing. One day while I

was waiting for some prints to wash, I looked across at the enlargers and

thought to myself that if I had the negatives in different enlargers and

simply moved the paper, the speed with which I could explore things or

line them up would increase a hundred times. That was the moment that

changed the way I worked with multiple images.

The other element, which was really a key factor, was that once I began

teaching, I ended up being the only photographer in an art department. I

was around creative people who were not photographers and who didnít have

their images occur in a fraction of a second.

Once I began exploring some of the options in the darkroom, I had

tremendous support from my friends on the arts faculty. But when I went to

New York to show people what I was doing they would be excited and say,

ďitís very, very interesting, but itís not photography.Ē

At the time photographyís highest form was seen in the work of

photographers like Paul Strand, Ansel Adams, and Edward Weston. If you

study art history, youíll see that there was a conscious effort to define

the separate mediums. Painting was oil on canvas, and sculpture involved

traditional materials like stone, wood or metal. And the photograph was

defined as a camera conceived silver gelatin print.

Chris and Larry:: Well, you certainly had the support of the art world.

You had a solo exhibition at the Museum of Modern Art in 1967.

Jerry: Yes, and that opened all kinds of doors; it was like being

blessed by the Pope. The irony is that John Szarkowski, who gave me that

show, later became a champion of photographers like Diane Arbus, Gary

Winograd, and Lee Friedlander and became less supportive of the

experimental tradition in photography.

Chris and Larry:: How did you start out learning photography?

Jerry: I went to Cooley High School in inner city Detroit. I had

terrible grades, but photography was a hobby. I worked part-time helping a

photographer at a studio where Iíd load film holders and carry a second

strobe unit when they shot weddings. Eventually, during high school, I was

shooting weddings.

Then I went to a two-year program RIT (Rochester Institute of

Technology) to be a portrait photographer. While I was there RIT expanded

into a four-year institution with both a photographic science and

illustration programs. Beaumont Newhall, who wrote the first popular

history of photography book and was director of George Eastman House,

began teaching. Then Minor White was hired. Minor would talk about images

that happened when the spirit came down and things like that. Until then

Ralph Hattersley had been the only RIT professor with a creative attitude

towards photography. Hattersley planted a lot of seeds, introducing me to

the concept that photography could be used for self-expression. Until then

I had thought of photography as doing assignments for others.

At the same time I was at RIT, Bruce Davidson was there. Pete Turner

was there. Carl Chiarenza, who went on to get a Ph.D. from Harvard in

photo history and Peter Bunnell were there. We had a critical mass for

open-ended thinking and discussion about what photography could be. These

individuals expanded my ideas about what photography could be. I really

feel blessed by that because had things gone differently, I could have

been a portrait photographer in Detroit.

After Rochester, I went on to Indiana University. I found myself very

disillusioned with the audiovisual program I was in. Then Minor told me I

should look up Henry Holmes Smith in the art department, and I started

taking some courses with him. I asked if I could change programs and work

on my Master of Fine Arts degree in the art department. Henryís first

response was ďIf you want to go on in art you have to be independently

wealthy.Ē I also had to take and pass an art history class to be admitted

to the program, which I did.

At the time you could have gathered everybody working with photography

as a fine art around a dining room table. Even Ansel Adams was still doing

a lot of commercial work. Photography as art had just not received a lot

of acceptance.

Chris and Larry:: It seems you were assembling your education like you

assemble your images. You were synthesizing elements of understanding from

the art world and the photography world. And at that time many people

still saw photography as a craft, not an experimental art form.

Jerry: Well your comment is right on. Thatís exactly it. Thereís

actually quote in Westonís Daybooks, where he goes to a museum and he sees

something that he really likes and thinks, ďGod, thatís something I could

useĒ. He thought that you use those things that are by rights of

understanding yours. So as various concepts were introduced to me, I would

think, ďThis is incredible.Ē Minor was the first role model I had who

truly did no commercial photography. He did creative photography and

taught and then he hung exhibits. I didnít know people like that existed

before. But I did, as you mentioned, bring together various aspects of my

educational encounters to create whoever I am, my identity as an

image-maker.

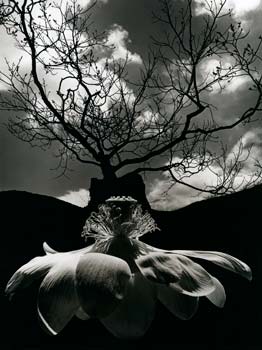

Chris and Larry:: Letís talk more about your creative process. When

youíre seeking what you have called a Ďreality that transcends surface

realityí, where do you begin? Where do you find the inspiration to choose

the elements and to assemble the picture as versed to taking a photograph?

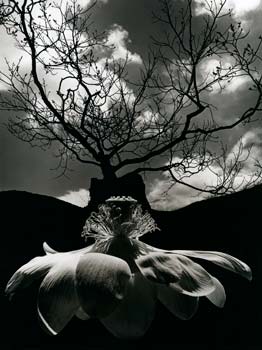

Jerry: My creative process begins when I get out with the camera and

interact with the world. A camera is truly a license to explore. There are

no uninteresting things. There are just uninterested people. For me to

walk around the block where I live could take five minutes. But when I

have a camera, it could take five hours. You just engage in the world

differently. If you can get to a point where you respond emotionally, not

intellectually, with your camera thereís a whole world to encounter.

Thereís a lot of source material once you have the freedom of not having

to complete an image at the camera.

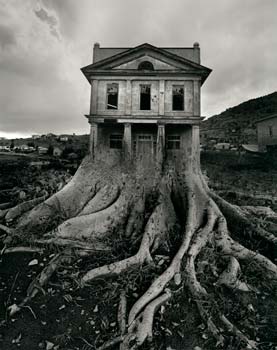

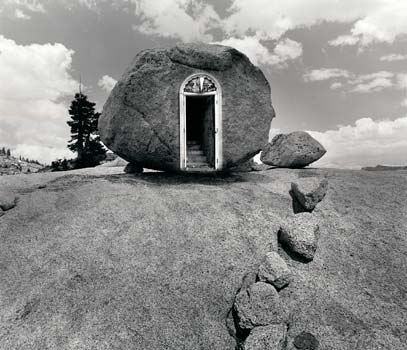

Of course as I developed a way of building images in the darkroom, this

also fed back into the way in which I saw the world. So if I find an

interesting tree or rock I think, ďGee, that could be a wonderful

background for something.Ē I begin to build a vocabulary based on things

that I encounter and then I start photographing things specifically for

use in my darkroom. I may photograph objects on a light box so they have a

white background or shoot things on black velvet so I can sandwich those

negatives later in the darkroom

But my initial approach is very non-intellectual. I just canít

emphasize that enough. Today there is a lot of conceptually based art that

begins with a particular theory and then the individual makes the images

to fit. Itís like an assignment, all planned and then they just follow

through and do the work. My approach is a lot less premeditated

Chris and Larry:: More of a spontaneous response to the world?

Jerry: Yes, and as a result I think my work has been very challenging

for some people to deal with. A lot of it is psychologically and

emotionally based. Thatís harder to write about than art that is

theory-based, as much contemporary art and post-modernism is. Plus, over

the course of the year I make some images that are very playful, others

that are very dark. Some of them no one would want to have on their wall.

But Iím the first audience, so Iím making them for my own satisfaction.

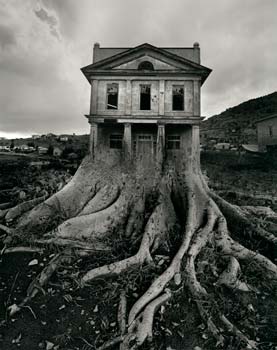

Chris and Larry:: Your work has been analyzed in terms of Carl Jungís

theory of the Collective Unconsciousness and its concept of Archetype. Do

you see your work that way?

Jerry: Well, yes. And, in todayís art world French philosopher Jacques

Derridaís theory of multiple meanings is also having an influence. Thereís

not a common syntax in a lot of visual material so people respond to it

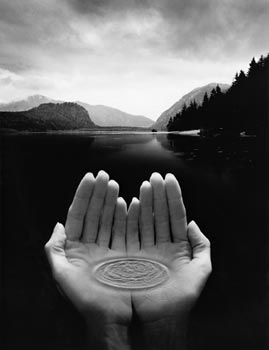

differently. When you have subjects that are really open-ended, like a

floating rock or a tree or whatever, that causes the consciousness of the

viewer to come up with their own way of connecting with that image. Itís

the audience that completes the cycle.

This, to me, is the wonderful part of photography and all the arts.

There is a kind of an emotional impact that can be felt when you see

certain images. It goes beyond communication, as we know it. Once you have

seen Edward Westonís photograph of the pepper, you canít pass them in the

grocery store without thinking about these things as aesthetic objects.

Westonís vision took a common vegetable to a new level. Thatís the aspect

of art that I like.

Chris and Larry:: Your work can be seen as very complex, or quite

simple.

Jerry: The joke that I tell when I lecture to art students is Ďwhat

happens when you cross a post-modernist with a used car salesman?í The

answer is you get an offer you canít understand. That always draws a big

laugh from the college students because theyíre required to read stuff

that is so complex that much of it doesnít make any sense, at least not to

me.

Chris and Larry:: Youíve spoken about risk taking and even how

self-doubt can be part of the creative process. Can you tell us more about

that?

Jerry: Well, I do think, particularly the way I work, the better images

occur when youíre moving to the fringes of your own understanding. Thatís

where self-doubt and risk taking are likely to occur. Itís when you trust

whatís happening at a non-intellectual non-conscious level that you can

produce work that later resonates, often in a way that you canít

articulate a response to. So much of what we consider knowledge involves

being able to state something in words. But there is another level at

which things impact us in a visual way that we really canít articulate a

response to.

Chris and Larry:: But nonetheless, we have a visceral or an internal

connection to some of the elements.

Jerry: Right. Thatís important. Iíve enjoyed teaching photography to

all kind of students from beginning to graduate level, and Iíve always

felt that walking around with their cameras gave them all kinds of

insights that were as important as spending hours in the library.

Chris and Larry:: You have for many years been the acknowledged master

of multiple printing and the art of physically collaged images in the

darkroom. Iíd like to pull a quote out of your new book, Other Realities,

which I think itís truly eloquent. ďI am sympathetic to the current

digital revolution and excited by the visual options created by the

computer. However, I feel my creative process remains intrinsically linked

to the alchemy of the darkroomĒ Weíve talked mostly about the aesthetic of

your work. Perhaps we can talk a bit about your technique and the digital

revolution that is going on in photography.

Jerry: Itís interesting how many people assume itís a competition.

Actually, Photoshop has generated a much broader audience for my work.

When I started people questioned if my work was really even photography,

it was so different than the Group f64 approach. Now there are new

audiences for my work. And young people who are learning digital skills

discover that the real challenge is coming up with an image that

resonates, first of all, with your self and hopefully, with an audience.

They can learn all these new techniques and think that theyíre easier to

use, but creating great images isnít about the tools.

Chris and Larry:: Your wife, Maggie Taylor, is a major digital artist.

Jerry: Yes, and sheís having huge success. Sheís a wonderful

image-maker. We both actively engage in the image making process, and work

a seven-day week. Itís not uncommon for her to be at the computer and me

to be in the darkroom many evenings.

I see the incredible options that Photoshop provides. But the bottom

line is the technique has to fit with ideas and images. I fell in love

with the alchemy of the photographic process and to this day, watching

that print come up in the developer is magic for me. I still find it a

wonderful, challenging experience. Itís also a kind of personal therapy

for me just to engage in that process. If travel and other work keeps me

out of the darkroom a couple of weeks, Iím not a nice person to be with.

Of course, in order to make art, the frustration of not working has to

be greater than the frustration of working. I try to push images as far as

I can. Sometimes I go too far, then as time passes, I think, ďThat was

stupid or overkillĒ or whatever. But you have to go to those places. You

canít just say, ďWe have an hour to talk on the phone, letís only be

profound.Ē You start wherever you can and then you work at it.

For me, every year I produce at least 100 different images and at the

end of the year, I try to sit back and look at them and find ten that I

like. Many years, itís hard to find those ten.

Chris and Larry:: Youíre making judgments when youíre looking at those

100 images that youíve created, do you solicit feedback from others as

well? Or is it mostly an internal dialog with your self?

Jerry: Actually, thatís a good question. I have some very wonderful

friends in academia and the arts. For years Iíd have these close friends

over to look at the prints and Iíd ask, ďIf you could have ten of these

prints, which ones would you want?Ē I didnít want a heavy intellectual

analysis, just personal responses to the images. The crazy thing was that

in most cases, there was not a lot of agreement. Obviously, there would be

some overlap, but itís a big world out there and people do bring their own

sort of aesthetic to bear. But Iím the one that ultimately has to decide

when I send things off to finally be in an exhibit or be published.

Itís not easy. Sometimes I have a kind of cognitive dissonance. There

are images that Iíve worked on for so long and have fussed over so much

that I think they just have to be good. The amount of energy I put into

creating them becomes a factor for me. Those are ones that, as time

passes, I might later reject. At other times, an image may just involve

two negatives and a simple blend, but people say, ďHey, this is a great

one.Ē Iím thinking, ďWell, that was a little too easy.Ē But thatís really

not the case.

Chris and Larry:: So when you build an image from multiple negatives or

from multiple images that youíve assembled, is that process additive or

subtractive? Do you start off with one and then add another, or do you

start off with a bunch of images and then say, ďLetís put these four

together and see what they doĒ?

Jerry: Itís always additive process. Itís hard to think beyond two or

three to begin with.

Iíll give an example. We were just invited to Seoul, Korea, for an

opening at a beautiful photography museum over there. We had one day out

into the countryside in one of their traditional towns and I had a chance

to photograph. I shot about ten rolls of film while I was over there. When

I came back, I processed those and the contact sheets then became the

foreground for me as I had just been there and made those photographs.

Then I started looking at different backgrounds, at combining things with

them. Itís interesting because once I start doing it, I remember other

negatives and things that might work with some of these things.

Now in the course of the last month, Iíve worked through most of those

negatives. I donít really sense anything else that I can do with them at

this point. But I can guarantee that five years from now, some of those

things that Iíve rejected will find there way into other images.

Chris and Larry: How much time and experimentation takes place

in the darkroom?

Jerry: Once Iím set up I need at least a six-hour block and preferably

an eight to ten hour block to do what I do. Computer people have this

advantage over the darkroom people by far.

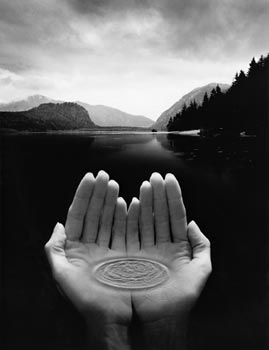

Two weeks ago in Yosemite I shot this rushing water hitting a rock in a

stream; it was like this wave in the middle of this river. Then I added a

water background with strange clouds. So at the end of the day, I have

this all set up. I have my chemistry. Iíve been testing with the different

enlargers. Thatís when I want the Holy Ghost to tell me with a whisper in

my ear, ďJust do three of thoseĒ. But as I age now, Iím 72, I think, ďIíll

never print this again.Ē I have too much going on. I want to keep making

new images.

I made ten prints and then in the middle of the night, Iím thinking,

ďThat shape that this water bows up in is like the shape of an eye.Ē I

hadnít taken the negatives out of the enlarger yet so the next day, I made

12 prints of the image with the rising water lighter and added an eye. I

liked it better. From my point of view, if I can improve an image 2%, Iíll

be back in the darkroom the next day.

Chris and Larry:: You mentioned the process of producing the work in the

darkroom naturally creates an edition. In fact, even if you just pulled a

negative out and put it back in, perhaps somebody with really sharp eyes

would notice that there was a slightly different orientation to some of

it. Do you then limit, or number editions created like that?

Jerry: This is a constant discussion in my life. All these gallery

people now want me to limit editions. But you see, I like the idea that

photographs exist as multiple originals.

Ansel Adams was a friend and I asked him back in the early Ď70ís about

this issue. Now this is a guy that made 50,000 negatives and he told me

back then that he had about 15 images that sold regularly Ė out of 50,000!

And his most popular image, Moonrise, he admitted to making over 1,000

prints. Iíll bet he made at least 2,000 prints of it in all sizes.

Editions made sense when people worked with engravings where the plate

wore down as prints were made. An early number of the edition had slightly

better quality. But thatís not the case with photography.

To me, itís a false way of creating value. But there are people out

there whose prices are going up and theyíre selling out editions and that

sort of thing. Iím not in that school. I figure Iím the only guy thatís

doing my prints. Once I go to the great darkroom in the sky, whatever

prints exist, thatís it.

Chris and Larry:: Still, your initial print runs are small.

Jerry: Iíll just make six prints of something usually. Why make more?

People say, ďIsnít it a problem to go back and reprint it?Ē Itís not a

problem - in fact the second time Iím creating these images I can focus on

the craft. The first time, youíre doing all the mental gymnastics about

what does it mean. When I reprint something I feel that I end up with

better prints than I did the first time.

Chris and Larry:: Do you ever scan your finished prints?

Jerry: I actually have people now that are scanning my work so there

will be a record of almost everything, certainly my most popular images.

In the old days if someone wanted to use an image I had to make copy

prints, 8x10 glossies on resin coated paper. But Iím amazed how itís all

done electronically now. Iím really blessed by having a wife with all of

these skills.

Chris and Larry:: Do you think it is easier to create images using a

computer?

Jerry: Itís equally hard and labor intensive to create an image on the

computer as it is in a darkroom. Believe me.

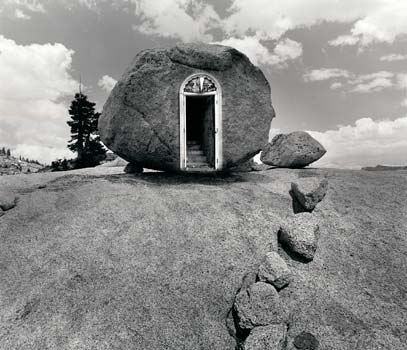

Chris and Larry:: The elegance way you bring images together is

impressive. A floating rock will have the right light and shadowing to

match the background and other elements appear give it context. That makes

even an implausible combination appear possible. Is your understanding of

light and perspective intuitive, or is that part of the intellectual

process?

Jerry: Its luck and intuition. Photographs in general have an inherent

believability, and the overall impact of an image can keep people from

noticing some of the slight discrepancies. Also, I prefer negatives shot

on overcast days as they give you greater flexibility.

Chris and Larry:: Do you still go out and shoot a lot?

Jerry: I tend to shoot more when we travel. I taught workshops with

Ansel in Yosemite for years, but really didnít get much time to explore

the park. Later, when my wife and I visited we explored more, going on

pack trips with other artists. I try to go every year. In September we go

to the high country, renting tent cabins the last week before snow closes

that part of the park. This year after Yosemite we went to San Francisco

for a few days, and then to Korea. I shot 23 rolls on that trip.

Chris and Larry:: What kind of equipment are you using now?

Jerry: Iím currently using a Mamiya 7 and a Bronica GS1. I also have an

old Bronica that Iíll use for the studio stuff but I want to carry the

lightest equipment that will give me the biggest negative I can get and

still use roll film.

Chris and Larry:: Have you shot large format or 35mm recently?

Jerry: No. The last time I shot 35mm, other than to make slides, would

have been in the early Ď60ís. And when I first went out and taught

workshops with Ansel, I found that I could shoot two rolls of film by the

time those people had set up their view cameras. They were trying to do

the zone system, which I think is overrated. Iíd much rather be

emotionally involved.

Chris and Larry:: Would you have any advice for those who would like to

pursue the fine art market and to use their photographic vision as a

creative approach?

Jerry: I know a lot of really wonderful commercial photographers, and

every one of them has their personal work in their desk drawer. Ryszard

Horowitz is a friend who does major high-end commercial stuff. And believe

me; heís certainly as creative as I am.

There are people like Duane Michaels and who can do both commercial and

fine art work. I have a lot of respect for that. People that are only

doing very personal fine art photography have to have some support system.

If theyíre well connected with a gallery in New York, that might do it.

But the art world is constantly changing. There are all kinds of art

movements that constantly come into vogue and then fade away. In

photography we have the phenomena of the huge color prints done by people

like Andreas Gursky and Thomas Struth. Theyíre amazing to see, but again,

thereís a point at which once every museum has one where does that trend

go?

I just read an article in last Sundayís Times where these curators are

talking. The one said itís sad how the emphasis is so much on new that

many artists who are doing some of their better work at their mid careers

or later careers are being neglected for the sake of constantly showing

the new, young kid on the block.

In my own case, if you went to the Museum of Modern Art and said weíd

like to see what you have by Uelsmann in the collection, theyíll have some

work, but itíll all be from the Ď60ís. Thatís when I was new on the scene.

Chris and Larry:: But you are still working, producing new images all

the time.

Jerry: To me, itís such a rewarding experience to be able to produce

personal imagery and have this kind of visual myth emerge over a period of

time, making images that can evoke a different perception of our world. We

are unique in that we can invent these realities.

Chris and Larry:: And perhaps on some deeper level, even understand

them.

Jerry: You bring up a very good point. The understanding can happen at

a non-verbal, intuitive level. There are images I have seen done by

students of mine whose names I do not remember, but I sure do remember

those images, so theyíve made an impact on me.

Chris and Larry:: You taught for 38 years, how did you challenge

students to be the most creative and effective photographers they could

be?

Jerry: The best teachers answer questions with more interesting

questions. That really sums it up. This is what Iíve learned after years

of teaching that education is essentially a question raising business.

I expected students to be showing work on a regular basis, because

thatís where a lot of the growth occurs, and to show work in process,

because people are a lot less defensive. Many places emphasize theory, but

I felt strongly that producing images was most important.

I tried to challenge people to define what they were doing, to try to

articulate what they thought they were doing. I realize I canít create a

verbal equivalent for my photographs, but weíve talked for over an hour

about what I think Iím doing and they should be able to do that.

I taught graduate students for a lot of my academic career. At that

level the students were really quite technically competent. Of course,

technique is something you can teach a person because there are specific

answers, but if youíre talking about a visual sort of aesthetic

experience, thatís different.

I always thought of it as a kind of psychotherapy for which I wasnít

trained. But itís important to always challenge accepted thinking,

particularly your own.

Chris and Larry:: Your lifetime of work shows the influence of that

approach.

Jerry: In the end, I aged but my students all remained the same age.

That was something that kept me much more in touch with whatís happening

in our culture and what was going on in the art world.