|

| |

|

| |

| Introduction: Joe McNally is an expert at

lighting big jobs with small flashes. Besides being a successful

commercial photographer, he also spends a great deal of time teaching.

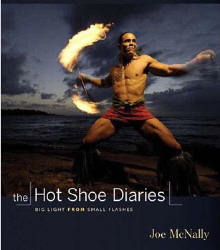

His new book is titled

The Hot Shoe Diaries and is a virtual how to for setting

up complex lighting using Nikon SB flashes. |

| Normally when we do interviews like this,

we also discuss in detail how some of the photographer's classic images

were taken. But Joe McNally's last two books,

The Moment It Clicks and

The Hot Shoe Diaries go into much more detail about the images

than we would have room to discuss here. LB |

| Chris/Larry: Many consider you to be

one of the best photographers working today. Can you give us some

background on how you started, what influenced you in your development as

a photographer? |

| Joe: I started off as a newspaper wire

service photographer, which is a great teaching ground for making you

improvisational. It enables you to think on your feet, rescuing pictures

when things are really going south and it teaches you a lot about the kind

of survival skills you need in the long run to stay the course in the

business.

I had the benefit of coming along at a time when the field was really

wide-open. Though there are many opportunities that you have now as a

photographer, there was a less pressure when I first started. I hit New

York and came under the tutelage and guidance of a lot of really good

established shooters and editors. It was a kind of atmosphere that if you

made a mistake, it wasn't a disaster, it was a learning experience, you

got back in the saddle the next day and you went out and you shot again.

Because of time, budgets, and other factors, some of that grace period

that you have to grow as a professional is truncated and more pressurized.

I did have a lot of ups and downs and disasters, the typical sort of stuff

that you would have when you start a career in New York. |

|

| Chris/Larry: You shoot a really wide

range of subjects and have used some pretty creative lighting to define

them. Can you give us an idea for how you approach your subject? How much

do you plan, how much is spontaneous? |

| Joe: It's always a mix. I do rely on

my well-developed sense of curiosity, researching my subject before hand

so I kind of know what I'm getting into. Then I imagine what the job would

be like and I imagine the picture. If I end up with a picture that was

close to what I imagined it would be, I would consider it a pretty good

day. |

| Chris/Larry: Do your images sometimes

go beyond your wildest expectations? |

| Joe: Sure, that happens. Serendipity

can, and does kick in on a regular basis. In terms of serendipity being so

extended or grand as to provide something that you couldn't have dreamed

up in your wildest dreams, that doesn't happen too often. The reverse

happens much more often, where you walk into a situation, you're keyed up

on a job, and you're thinking, oh, maybe I'll do this or maybe I'll do

that. Then, in the very first ten minutes you're on the job you realize

none of that stuff is going to happen. The subject is not cooperating, the

weather stinks, the location is bad, there's a limited amount of time, or

whatever might have happened to affect the outcome.

I was doing a portfolio for Sports Illustrated a couple years ago, and

I ended up having to shoot a picture in three parts and have the magazine

put it together back at the shop because I missed my connection in Salt

Lake City. It's the practical aspect of being a photographer. I couldnít

get to the location early enough because I missed my flight because of a

plane delay, and that put me back on my heels and the shot that I had

imagined that I could do in one piece, went out the window and I had to go

into [when I teach classes I always call it] triage-mode. What do you have

to do to save this patient? You walk in and that picture is dying on the

table. What do you do to resuscitate it?

That's where, again, I harp back to my early experiences working the

streets of New York, that you have that rolodex of survival in your head.

Options. Quick fixes. I'm not saying that you want to have the job end up

like that all the time. But it's a good thing to develop as a photographer

because it does keep you fast on your feet and enables you to procure a

reasonable, or even good frame out of a bad situation. Then, you live to

fight again another day. You rev up the imagination for the next job. |

|

| Chris/Larry: Your confidence and ease

in complex situations is clear. You seem to have mastery without any ego.

What allows you to bring all the elements together? |

| Joe: I think it partly relates to the

diversity of work Iíve gotten. I've been a generalist my whole career and

been thrown everything including the kitchen sink. You would call some of

the assignments, problem solving in nature. For example, Iíve shot stories

for National Geographic for 25 years and some of those stories might make

a lot of the other photographers run in the opposite direction.

I've done highly technical stories about science and space. To do that,

you need to have a fair amount of imagination, and then sometimes that

imagination leads you to a solution. Because what you're doing is trying

to take a concept or an idea, or some sort of scientific theorem,

something that most people are not going to have an immediate

understanding about, and translate that into a photograph that's going to

grab somebody. You have to imagine yourself in the reader's seat. I always

view the reader as who I serve.

I'm not serving my ego, I'm not serving even the magazine Ė I mean,

obviously, I am. But at the end of the day, if you've been able to move

the reader, the consumer of your picture, then you've done a good job.

I look at a story from the perspective of a naÔve viewer. For example I

don't know much about telescopes but I've done two big telescope stories

for the Geographic. Most people don't know much about telescopes either.

If I look at it a certain way and think that would be cool, then I imagine

the reader might have the same reaction. So that's the way I pursue it.

It's kind of simple really and sounds almost stupid, but it's the way you

find pictures. |

|

| Chris/Larry: What about youíre own

projects or self-assignments? Do you still think in terms of how people

might understand or perceive the end result, or is it a process of playing

and discovery? |

| Joe: A combination; I do try to play

with pictures. And I always counsel young photographers to have fun out

there. First and foremost, you're in this blessed position. You're out

there in the world breathing the air and not in an office. That's a really

privileged place to be. And secondly, there's so much pressure on the

business side of photography, that if you really thought about it too

much, you'd probably just stop dead in your tracks. The main thing is to

enjoy yourself and have fun.

I always quote Jay Maisel, who's a good friend and wonderful teacher.

He'll look at somebody and say, "I don't think you cared about shooting

this picture because you're not making me care about it when I look at

it." That's a pretty pungent criticism and it's also very accurate. You've

got to pursue pictures out there. Great pictures, or even really good

pictures, don't drop from trees. They're sometimes a product of a lot of

hard work, a lot of tenacity, a lot of problem solving, and then that

final fill-up of good luck or good fortune. That's the guy behind the

curtain stuff and readers don't want to see that. They want to look at a

picture and view it as effortless, like, wow, that's really cool. That's

what the viewerís first reaction should be. It shouldn't be like, oh, this

must have been a lot of work.

So there are a lot of different threads that come together when you're

finally pulling a picture out of the fire. You're trying to make it

accessible to people, and also intriguing enough for them to spend time

with. |

|

| Chris/Larry: You seem to be doing an

amazing amount of shooting, teaching, writing as well as keeping a

detailed running commentary on your blog. How do you keep so connected to

your work? It canít all be fun. |

| Joe: No. Part of the fast pace is

about the nature of photography today. You're making all of this come

together as an enterprise, as a living, not just as a hobby.

I went to school to be a writer. My books and the blog have enabled me

to re-embrace that art form. I really have a good time doing that because

I enjoy writing. If truth be told, I enjoy it almost as much as I do

photography. You sit down and plan to write the story of what just

happened to you in the field, and it's inevitably kind of ridiculous,

humorous, and mildly compelling, because itís the stuff that happens to a

photographer in the field.

We were teaching yesterday (Photoshop World Boston) and we had these four models sitting on this

WWII jeep in front of a Destroyer in the Boston Shipyard, we didn't know

it, but the place was closing. So this guy just walked over while I'm

shooting, I had 75 people around and these models on a jeep, and the guy

just came to the jeep, turned it on and said Iíve got to take the jeep.

There went the prop. The class just convulsed; I turned around and said

this is what happens on location. Everybody can send you down the tubes on

location, from your subject to the freight elevator guy. |

|

| Chris/Larry: So many of the images you

create seem magical, even when you are teaching a workshop. Can you tell

us about your though process, give our readers a sense of how you connect,

overcome problems, and deliver such excellent work? |

| Joe: Let's first get something on the

table; it's not all magical work. Sometimes you have your ups and downs.

It's like playing a sport; you have your good days and bad days. But I do

think the core of what keeps me going forward is basic love and enthusiasm

for being a photographer.

I enjoy the coupling of shooting for clients and teaching. I shoot when

I teach and people in a class expect you to produce something that's

really worthwhile as you demonstrate. Iím shooting live so it's up on the

screen in front of 300 to 400 people. That's what I do all the time. Other

photographers have come up to me and said, "Man, I can't believe you do

that. I would never let them videotape me live. I would have it rehearsed;

I'd have it in the can." I just accept that kind of pressure, itís part

and parcel of being an assignment photographer. I always caution people

that we're going to make a series of mistakes and find our path through

our mistakes; I'm very unabashed about that. I make mistakes all the time

and that is a very valid way to approach any location scenario.

Your digital contact sheet shows your thought process, from the first

frame where you're just doing location assessment and following that

through, it's your thought process right there. When I came up

photographically, really good photo editors couldn't care less about your

portfolio, you know, your greatest hits. They were like yeah, sure kid,

yeah that's nice, but let me see your contact sheets.

Your contact sheets are the roadmap for what you're thinking when you

have a camera in your hand. If you go through a digital take when you are

building a solution, lighting or whatever, you go back through that and

youíll see the photograph build. You see frames where you misfired, frames

where things were off, and then finally, usually through this process, you

establish what I refer to as clarity of thought.

I teach a lot of lighting; people are messing with the lighting, but I

say look, before you start messing with the lighting, you got to mess with

the picture. Where the camera goes is much more important than where the

light goes. Once you figure out where the camera goes, then putting the

light in an effective place is much easier. |

|

| Chris/Larry: When Nikon introduced the

Creative Lighting System in 2003, they asked you to create the DVD Speed

of Light, which really showed what the system could do. Did it take you

long to grasp and master CLS? |

| Joe: Yes and no. Not to come down the

middle there, but no in the sense that once you crank through the buttons

and dials the first few times, it becomes pretty intuitive. Physically

working the flashes is not too much of an issue. Wrangling good light from

small spectral light sources like these becomes the larger issue for me.

How to craft that in the same way as if you were shooting bigger studio

lights. The CLS, as Nikon brought it out, is a truly a wonderful flash

system because it works.

Does it have glitches, ups and downs, misfires, and stuff like that? Of

course, every camera and every system does, and I think that that's where

some folks get a little frustrated. I always remind people that it's a TTL

system, Through The Lens, so when you point the lens at something, all

that exposure information is streaming into the camera. You shift your

angle, change your lens, you're going to get a different stream of photo

information or exposure information, which is going to send a different

message to your flash.

Therefore, the flash will react in a way that it thinks is appropriate

but it might be way off and you say hey, wait a minute, it was fine a

minute ago. Then you start to identify situations where TTL is going to

not work so well, and other situations you walk in and see immediately

that this is tailor-made for TTL.

The nice thing about the lights is that by working with the information

that's occurring at the moment of exposure, you've got a tremendous amount

of intuitive technology to use, which is pretty great. I always regard it

as a gift. Young photographers sometimes get frustrated with it and I'm

like hey, wait a minute dude, you know, not too long ago we were out there

with a couple of rocks trying to make sparks. This is very sophisticated

stuff that we're doing now, so just roll with it. |

| Chris/Larry: You convinced National

Geographic to let you shoot The Future of Flying story entirely digitally

back in the two megapixel era of 2002. Can you tell us a little bit about

how you convince your clients when you want to take them to the next

level, a place that maybe they don't even understand? |

| Joe: I think part of our mission is to

educate our clients, to make them aware of possibilities, to talk them

back off the cliff of where they have always been standing, and say look,

you don't have to jump that way this time, you can maybe do something

different. I've been really blessed to work with some really great art

directors. A couple of commercial clients I have an ongoing relationship

with and they really are open to that because the best relationship is

that the client picks the photographer because they feel this photographer

can bring something to the party they really are interested in. |

|

| Chris/Larry: What about your workflow?

Can you tell us a little bit about the technical side and how you review

and post-process your final images? |

| Joe: My camera system is Nikon and I'm

shooting D3's. I shoot Lexar cards. All the imagery is organized in

Aperture libraries and we use Aperture as a management program: sorting,

pulling, slideshows, and this and that. I do raw finishing in Nikon

Capture NX 2 and then the final shaping and presentation of the imagery in

Photoshop CS4. My assistant and I have MacBook Proís and we have three

Macs in the studio with the Cinema Displays and a Wacom Cintique. Let me

also issue this disclaimer, I don't do much retouching. I'm not good at

it; I've tried off and on to learn about it, but I've been staying kind of

busy, so it's a little hard and a little elusive for me. If there is any

post-processing and finishing to be done, my assistant does it and we

consult with each other. |

| Chris/Larry: Do you have any advice

for photographers who are struggling now to maintain their love of

photography and their professional standing, things that have helped you

deal with these difficult economic times? |

| Joe: Tenacity is definitely part of

the equation, always has been, probably even more so now. There's a lot of

competition out there and there's a lot of re-trenching on the part of

clients. Money that they might have spent in a more freewheeling way,

they're watching much more carefully and they're deciding to go with last

year's pictures or stock images as opposed to generating work. I'm facing

the same thing, absolutely. I have a new story coming out for Geographic

in June. I shot two stories for them last year and I haven't heard from

them so far this year. We'll see where that goes.

When I was a staff photographer at Life Magazine, it was an interesting

and blessed position. I really had kind of a benevolent patron who would

listen to my ideas and fund them if the editors found them worthwhile.

Now, so much of that is back on the photographer's shoulders, finding

funding, going forward, and generating ideas. It's pretty madcap in lots

of ways, the whole idea of trying to make a living as a photographer now

is a high wire act. Tenacity is a huge part of the equation as well as the

ability to maintain good humor and a positive outlook despite the fact

that you're hearing the word "no" a great deal.

You have to be able to keep moving forward and you have to keep

apprised of new technology. To have a market presence as a photographer, a

blog, or certainly a web site, is required. Itís a way of communicating

and letting people know that you're out there.

Also, try your best to remain aggressive, even in lean times. I think

it's important for photographers because if you look through your

portfolio, your best pictures have almost always occurred when you took a

risk. Whether that is creative, emotional, financial, or whatever it might

be, and nowadays the word is to be risk-adverse. You know, shutter your

doors, close down, do nothing, and weather the storm. But I would argue

that no matter what, to the best of your ability, you have to keep

creating work and take chances. You have to keep pushing your own envelope

or you'll wither right along with the economy. |

|

Check out Joe McNally's

blog and

web site |

|

|

|

Contents of the Interview © 2009 Chris Maher and Larry Berman

Images and text are protected under United States and International copyright laws and may not be reproduced, stored,

or manipulated without written permission of the authors.

|

| |

| Chris

Maher

PO Box 5, Lambertville, MI, 48144

734-856-8882

|

Larry

Berman

PO Box 265, Russellton,

PA 15076

412-401-8100

|

|