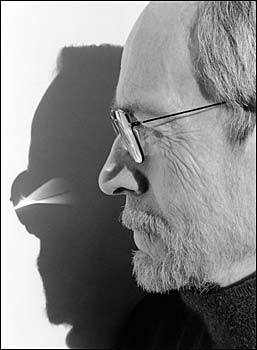

Chris/Larry: Let start by talking a little bit

about how you started out. You studied photography at Rochester Institute

of Technology, graduating in the class of 56. There were some great

photographers in your class, people like Paul Caponigro, Bruce Davidson,

and Jerry Uelsmann. How did this formal education in photography affect

your vision, your ability to create the amazing color pictures that you

are known for?

Pete: Our class was called the ĎGolden Classí as I recall. A lot

of people studied with Minor White and Ralph Hattersley, wonderful

teachers. In fact I was talking to Weston Naef, curator of photography at

the Getty Museum and he said Ďyou know, somebody ought to come up with the

idea of doing a group show of all you peopleí. It actually stuck in my

mind that we are all kind of different disciplines. That kind of says

something for RIT back in that period that there was a very opened minded

group of teachers. So you can have a Jerry Uelsmann, and a Bruce Davidson,

and a Ken Josephson, and a Carl Chiarenza, and a Pete Turner, all working

together, however, all going in very different directions and being

encouraged to do so.

Chris/Larry: Well you had, as you say, some great teachers. In

addition to Minor White and Ralph Hattersley, you also had Les Strobel and

Robert Bagby. There had to be quite a difference in the way Les Strobel

approached reality then Ralph Hattersley.

Pete: Right. Bagby was wonderful with color and he came from

like a very commercial New York background. Theyíre just really great

people, Dick Zakia was also in the class.

Chris/Larry: Can you trace in any way the influences of those

people on your work? Did they impart anything unique or any kind of world

vision that you were able to work with later?

Pete: I canít really think that it worked like that. I looked

over at what Bruce was doing, and went on to do, and I liked it very much

but it really wasnít my style. Jerry Uelsmann was photographing very

subliminal type of images that were about things we dream of, kind of

surreal stuff, and that wasnít really where I was going. Everyone was a

little different. Carl Chiarenza was into his graphic, black and white

rich type of thing. Paul Capronigro didnít actually go to school there but

he was studying under Minor White at the same time so he was around. Peter

Bunnell was also in that group that we graduated with. Heís a historian

and a curator. It was a diverse group.

Chris/Larry: Well, what about influences of other people? There

is a surreal edge to your work. Did you study the work of Rene Magritte?

Pete: Absolutely, our teachers made it a point. They said you

have to go to museums and study paintings as well as photography. Study

the visual arts. And Magritte was also a wonderful influence. Maybe the

person that really influenced me the most was Yves Tanguy. I just loved

his paintings of these very weird and exciting shapes on the beach and

things. Some of my composite work definitely drew from his arena I would

think.

Chris/Larry: After school you had other opportunities. You went

into the military after RIT, is that correct?

Pete: It was compulsory. Back then we got drafted and they

didnít waste much time. I remember graduating, and soon after getting my

notice from the President of the United States. Having a degree, I could

have become an officer but I decided to be an enlisted man, a private,

because you got out in two years. If you elected to go the other route

then you had to keep going to meetings forever and you could get yourself

shot at more frequently. I was lucky because I didnít have any wars to

fight.

Chris/Larry: We read somewhere that there were some famous

people in your Corp in the military.

Pete: In the Army Pictorial Center, yes. There were some

celebrity types because they got into pictorial center. I was lucky. I was

stationed in Indianapolis as a photographer on the base. One of my

assignments was to photograph a General over there next to a sculpture.

And he really loved the shot, called me over to his office, and said you

should meet this Major Briarley over at the pictorial center in Long

Island City. In fact, you should be working over there, not out of here.

He picks up the phone and calls his buddy in the Marines and the next

thing I know, Iím on a train going to New York. The Army Pictorial Center

was unique. We were in the Second Signal Combat Team, which was joint

services. That meant we could work with the Marines or the Army. They

could use us on an as needed basis. I got to run a type C color lab when

it had just got invented. So Iím making all these prints and its part of

my on the job training. My assignments would be to take a subway ride into

New York, shoot a lot of pictures, come back and print them to keep the

mechanism going. Meanwhile Iím building a heck of a portfolio.

Chris/Larry: That sounds like a tremendous opportunity to work

in color when color was very expensive and pretty rare really.

Pete: Incredibly rare at agencies. They only got to deal with

dye transfers. Here comes a kid who walks into an advertising agency with

120 color prints under his arm. That got some attention.

Chris/Larry: What were the initial responses when you went out

looking for work at magazines?

Pete: You know, amazingly well. I had done a respectable

shooting at Ringling Brothers Barnum and Bailey Circus at Madison Square

Garden right after I had gotten out of the Army. I had used some new

high-speed color films that had just come out. It was real fun and I

brought them up to Alan Hurlbert and he liked them and said lets hold onto

these. And then the Africa trip came but when I came back they published

that circus story. All of a sudden Iím getting a lot of promotion real

quick.

Chris/Larry: What magazine was that published in?

Pete: In ďLookĒ.

Chris/Larry: Thatís certainly starting at the top.

Pete: Well, when I was a kid my father always said, Ďdonít be

afraid to aim high, you can always aim lowí. So I knocked on some doors

that I thought were pretty high. Some of them I got kicked out and others

I got embraced. I was really lucky to meet Harold Hayes and be invited to

work for Esquire Magazine. He was one great editor. You wouldnít have

dared go off on a shoot and not come back with something spectacular.

Chris/Larry: When you did your Africa journey in 1959, you

certainly came back with some spectacular things from that. Can you tell

us a little bit about how you got that assignment? It sounds like a real

plum.

"Smiling Woman" |

Pete: Well, it was really the big break, the

seminal break of a lifetime. I was a kid who had just gotten out of

the Army and I was approached by the people from Airstream Trailer. I

had been doing some stock work through FPG at the time, the Freelance

Photographers Guild, with Arthur and Hennrietta Brackmen. They

introduced me to Pat Terry of Airstream. They said Ďhere is this kid,

he just got out of the Army. He doesnít mind about going to Africa for

half a year. That would be fun for him. He doesnít have anything to

hold him backí. Itís true. When you get out of the Army after a couple

of years of living in barracks with fifty or a hundred people mopping

toilets and whatever, itís not a big deal to get in a trailer. So when I got approached it was good deal and I said, gee, Iím gonna

get wonderful subject material. I really got excited and I guess my

excitement caught on because the next thing I knew I got hired. When I got

that assignment I went to Geographic and told them what I was about to do

so they assigned me to do a story to shoot some of the natives. The funny

thing is the story never ran, but they offered me staff afterwards.

Chris/Larry: And did you take them up on this?

Pete: No. I thought about it but the real estate of Geographic

was kind of small in those days. You had ďLifeĒ and ďLookĒ and I liked to

see my pictures big.

Chris/Larry: Lets go back to Africa. Camera equipment in 1959

was a lot more limited than it is today. What kind of equipment and how

much film did you take?

Pete: I took 300 rolls. All Kodachrome. Some high speed

Ektachrome. All 35 mm. I brought three Nikon SP cameras, rangefinders.

Because other than that you were into view cameras but Nikon had the best

glass. As a matter of fact, I still use Nikons today.

Chris/Larry: Speaking of glass, what were the lenses that you

had for your SPís?

Pete: I think there was a 35. A 50 and 105 for sure. And for a

long lens I had a 135.

Chris/Larry: Of the 300 rolls of film you brought to Africa, how

much did you actually shoot?

Pete: All of them.

Chris/Larry: Did you run out before the trip was over or did you

pace yourself to the end?

Pete: I worked it out pretty good, but I think I had to still

had to get a few rolls sent. Geographic is really good about that and they

had ways to do it. But itís not easy to get film shipped to Africa.

Chris/Larry: Especially in í59. How did you store your film?

Pete: The Airstream Trailer company built a special vehicle for

me. The drinking water tank in the vehicle was somewhat like a vertical

basement water heater, except this laid horizontally under my bunk. They

arranged for me to have enough room on either side and on the bottom so I

could pack my film. The water kept the temperature cool so when we got

into the equatorial regions of the Congo my film wasnít burning up.

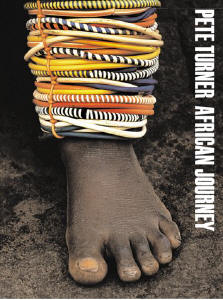

Chris/Larry: You have an interesting juxtaposition of two images

in your African Journey book, one of a Ndebele womanís brass rings on her

leg shot in í59 and another of some brass rings around a ladies neck that

was shot in í95. Thereís interesting similarities and differences. When

you intentionally revisited that subject what were you, as a photographer,

thinking?

Pete: I went back three times to the Ndebele people. The first

time was in 59 and I lived in the village for about a week and there is a

little story about it in the book when the chief made me invisible. The

second time I went back in 1970 and the chief had died. Most of the people

no longer existed. Instead of straw roofs most of the roofs were

corrugated tin. They had lost their charm. In 95 when I went back to the

same general area near Pretoria where the Ndebele people live, there was

no longer a village. There were a couple of ladies who kept the Ndebele

wall painting tradition alive and one of them had really nice rings and I

photographed her neck.

Chris/Larry: Itís interesting to see the how strong and clean

your technique was in 59. You had a real grasp of using the material

because I think either image would be comparable to anything anyone with

skills could create today. I think the combination of seeing how you

approached it in both ways is very instructive. Speaking of other things

that you shot in Africa, that was still very formative point in your

career. In the book you speak of an epiphany, a moment when you discovered

the difference between finding a photograph and making one. You

specifically mention your Rolling Ball photograph.

|

"Rolling Ball" |

Pete: That's as clear as yesterday to me. It

happened in the middle of the Nubian Desert, where there isn't much to

shoot. You go on and on and there's little shiny black rocks and sand, and

little textures when the wind blows. And I had seen this hut with a

triangular roof on it and thought, oh gee, that would be great to shoot

because it was something where there's endless nothing. So around 4:00 in the afternoon, sunset would be around seven. It was

still about three hours early I stopped there. I said, well I'm going to

set up here. This is where I'll hang out tonight. And I'm going to shoot

this place cause it looked kind of graphic and nice. The story is in the

book. I walked around it and as I walked around it at different distances

I realized that the sphere of the sun as it was setting would move. I

could make it move visually along the edge of the triangle of the roof.

And all of a sudden it was like the birth of an idea. I mean it was so

simple. All of a sudden I'm saying whoa, I mean I'm not just finding

things, I'm now making the photograph different by moving backwards and

forwards. I was using a 105 lens, and positioning the sun in different

ways and it's something I had been doing intuitively but I hadn't really

realized it. But this evening when I was working I realized that this for

me was the way to go. I don't have to just say, well OK this is it, and

walk away, that there's always the opportunity to develop the idea further

and make photographs better in my mind.

Chris/Larry: When youíre making pictures like this are you using

a tripod or just walking around?

Pete: Just walking.

Chris/Larry: Youíve said youíre not a purist in terms of

reality, that making a picture is the way you do it. That even includes

moving things around, introducing unexpected objects. Like the tin cigar

tube you shot in the Maasaiís ear in 1970, or that wonderful cannonball

shot in Mozambique in 1980.

"Cannonballs" |

Pete: The cannonballs were really great because Iím

leaning against them and they actually moved. And I said, Ďoh my Godí,

because Iíd been to a million forts and I hate forts because theyíre

boring. But my guide kept saying you have to see our fort. It was

gorgeous, all white washed and everything. But then the cannonballs moved.

I could pick one of these guys up and move it around and all of a sudden

it was like a chess set. A visual chess set.

Chris/Larry: Was it filtered in any way?

Pete: Yes. I always like to carry a few rolls of incandescent

film with me, type A or type B film. Especially at dusk because it

enhances the blueness.

Chris/Larry: When you are shooting now do you still use that

technique, or do you shoot with the knowledge can carry it further

digitally and therefore shoot regular film? Is your choice of film as

critical now?

Pete: No. I usually stick with daylight film. Digitally you can

do anything afterwards and I would rather have the picture neutral. Like

if I were to shoot Cannonballs today I probably would have shot it

strictly with daylight, Once you change a picture to blue it is pretty

hard to bring back all the colors again. The colors disappear.

Chris/Larry: Is there any limit to the way you can recompose an

image in reality? Does this extend to the way an image can be digitally

altered? Are there any limits in terms in manipulating the image? There

are some photographers who are purists and feel that there is a certain

point where they should not go beyond. Do you have any points that you

have should not be passed?

Pete: Sure, I think that thereís a certain point that you should

not go beyond. Like, ďPete Turner African JourneyĒ I decided would be a

real book in terms of non-manipulation of reality. People might say that I

manipulated color here and there and intensified things, yes. But there

was a certain degree where I stop. I have other African pictures, many of

them which are, youíd say are digital, or composited. None of those went

in this book because I wanted to keep the book pure. To be real

photographic, because you know weíre living in such an age where it is so

easy to make photographs that are not real but are like composites in our

minds. I kind of like to buck that trend and say hey hereís a book of real

pictures, so these are real.

Chris/Larry: In your studio work youíve got some wonderful

pieces with geometric shapes with color fields and such. Were those

created in camera?

Pete: No. Most of those were done on a Maron Carrol optical

printer or prior to that using an old Repronar with a Nikon body and lens

on it with a souped up strobe system, to do compositing.

Chris/Larry: Have you ever been tempted to pursuing that kind of

a vision digitally? Just starting entirely working with polygons and

various computerÖ

Pete: Sure, you know it is always interesting to play around and

my work has a lot of different facets to it. But in the African book I

wanted to keep pure photographic. And not get into manipulative digital

work.

Chris/Larry: In the past youíve done some intriguing in camera

double exposure work. The image you took of the Statue of Liberty with the

aircraft in 1962 comes to mind.

|

"Statue of Liberty Double Exposure" |

Pete: I used to do a lot of in-camera multiple

exposing and I used to use different filters when I was doing that. Like

maybe trying a red filter, a blue filter, an orange filter. And maybe

making two or three exposures on the same frame. Marty Forsher was a

really good camera repair person and he had created this device where I

could make double exposures on my Nikons before they built that feature

in. What I liked about it was

that I could do it after the fact in a duplicating machine. But I really

liked the idea of the surprise when you got the film back (laughs). Lets

say there was a lot of risk involved but there was really a thrill

involved at the same time because you never really had it nailed down like

after the fact in post where you can use grids and you can position things

absolutely where you want. I did have some tricks though. Sometimes Iíd

run the roll through the camera a couple of times, and sometimes Iíd do it

on a frame by frame basis. But one of the things Iíd do, like with the

Statue of Liberty, is go in tight on one exposure and then pull back and

go wide on another so that allowed these different color fields to build

up on each other.

Chris/Larry: And then when you were working in this way, when

you were doing sequences and trying it, it must have been pretty exciting

to see the stuff on the lightbox afterwards. That must have been the point

of discovery right there.

Pete: It was total experimentation without any guides or grids.

Just instinctive feeling that, well if I make the Statue of Liberty in

this part of the exposure, and make the next exposure smaller, and

positionedÖ I did drawings actually. I had a rectangular notepad with me

and I make notations.

Chris/Larry: Were you using a grid screen in the camera?

Pete: No that was before that. They didnít even have them then.

Chris/Larry: Then of course there was the happy accident or the

serendipitous moment when a jet plane would fly into the frame as you were

shooting and then that would be juxtaposed. There were probably a lot of

elements that appeared and ended up as part of the process.

Pete: Well yes, a bird or a jet, those were always welcome

surprises.

Chris/Larry: Digital cameras, of course, donít allow double

exposure but Photoshop makes the combining of images practically into

childís play. How has this allowed your creativity to explore new realms?

Or is that the ease of creation now taken some of the mystery or chance

out of it?

Pete: Itís taken the mystery and chance right out of it. I made

a decision a few years ago not to actively pursue composite work simply

because there are so many people playing with these tools, that I just

didnít really want to be in that lineup. And with the work that Iíve done

earlier, some people call me the pre-computer photographer, the guy who

did composites in the pre-computer era.

Chris/Larry: Tell us about how you shoot, how you relate to a

subject, about your state of mind or the energies that you feel.

|

"Cheetah" |

Pete: Well, usually Iím pretty

selective, especially on a personal project. Iím pretty selective about

what Iím going to shoot and Iím going to go and Iím going to do that. Like

with the Cheetah picture which is very green and rich and there is a lot

of motion to it. I wanted to photograph a cheetah that day and when we did find that

cheetah it was walking along a path and I was in a Land Rover. In between

the path he was kind of walking and the Land Rover was an incredible

bamboo, whole masses of bamboo that seemed to go on forever like along a

stream or something. But you could see through them partially. So I had

the driver match speed with the cheetah and the cheetah was kind of just

walking, you know, doing what Cheetahís do, staying the same distance,

which was great. So Iím just shooting like a 500th and Iím shooting and

Iíve got half roll already and Iím seeing bits of pieces of him, and Iím

saying thatís really interesting.

Chris/Larry: With the 105?

Pete: Probably a 105 or a 200 or something in that range. You

know, after I got a certain amount of film in the can so to speak, you

start saying what do I do now? The motion is really great and we had

something going on between the driver and the cheetah. They were really

locked in to the same speed and I said lets take this down to like a

125th, and I shot a few frames. I said, why not try a 60th and I shot off

a few more and then I said the hell with it why not go to a 15th, you know

(laughs), Iíve got enough pictures. I shot that roll off and I reloaded

and I kept right on going. I straddled the exposures around a 30th, a 15th

and an 8th, which was too blurry. But I shot another whole roll.

Chris/Larry: Just experimenting with the possibilities.

Pete: Right, and youíve got to realize that I am in Amboseli

Park, in Kenya, in Africa. And it is 1969. So, Iím shooting this and I

shot it, and thatís the way I work, sort of intuitive, winging it a bit.

Get back to camp, forget what I shot that evening and the next day Iím

shooting something else I donít remember. I forgot all about it. It wasnít

till like three four weeks later when Iím back in New York looking at the

processed film and here come up two rolls of cheetah. First frozen looking

pretty static. And then all of a sudden there is some liquidity going on

and then all of a sudden itís like, Ďoh my Godí, the motion, look at the

feeling. A lot of time would go by. Things are quicker today especially

for digital, people using digital, instantaneous. But back then a month

might go by, and you might even forget what you had shot.

Chris/Larry: Itís interesting too, to note the color of that

particular shot, I saw it published in your Pete Turner Photographs book

(1987) and of course you put it in your Pete Turner African Journey Book.

Pete: The reproduction is awful in the first book.

Chris/Larry: In the first book it is extremely green. It is

bright green. I think the information in the first book says you used a

cc30 green filter to push it towards the green, where is in your African

Journey Book the cheetah is much more tawny. Would you say that is just a

reproduction issue or was that more your vision?

Pete: That was the reproduction. In the Pete Turner African

Journey book the picture was reproduced exactly the way that I intended it

to be. In fact I was on press for that book. On the other book I was not

on press. That picture was probably the worst reproduced picture in the

Turner Photograph book, the picture of the cheetah. Every time that I see

it I cringe. Cause it looks like printerís ink, you know.

Chris/Larry: Letís talk a little more about the way you approach

your color work. When you are working with a colorful subject how much is

pre planning and how much of that is spontaneous reaction to your subject?

Pete: Well, it depends. When I have the opportunity Iím usually

excited by color. Color is what attracts me. I think the reason Iím

successful with color is that itís a level of taste. Itís a little bit

like Christmas tree lights in Los Angeles. In LA youíll see Christmas

trees that are done in silver with all sorts of lights on them and it will

yank your eye open to it. And once you look at it you say, my god this is

ugly. Color is hard to control. There are very few people who can really

control it. I donít know if Iím answering your question. Iím talking more

about color.

Chris/Larry: Knowing the difference between strong colors that

are gaudy and strong colors that have impact and tell a story. Thatís

really your hallmark, thatís what you have accomplished so well, yet, as

to describe it and how that vision has come to be is something I think

people would be very interested in.

Pete: Itís a matter of taste. Itís a matter of what feels right

to me and I donít like gaudy things. I advise photographers not to put a

polka dot filter on their lens simply because it would be a wild color and

people will look at it. You might get their attention but theyíll look

away because it has no content, it wonít hold you.

Chris/Larry: We also noticed that you used shadows to create a

lot of black negative space.

Pete: I like mystery and I think mystery is an important part of

what I can give a picture when I am working.

Chris/Larry: Lets talk about your shot ďNew DawnĒ, the shot of

the volcano in 1973. That is a phenomenal image. Thereís of course the

negative space and the incredible color in the sky. Can you tell us a

little about that when you were working with that subject? What lens you

chose, did you filter the image? How did you come up with such an

amazingly dramatic image? Obviously a volcano erupting over the town is a

dramatic event, but your handling of it was astounding.

|

"New Dawn" |

Pete: Well, it was luck. Favoring a person that was

well positioned. We were pretty battle weary, I had been on the island

about 20 hours. We were in a house covered with tin with pieces of lava

raining down all night long. People were trying to nap. I had taken enough

night shots and was just starting to doze off when somebody shook me and

said you better get out there, itís incredible. I ran around the backside of the house and hereís this incredible arc

of lava spewing, going off to the left side of the volcano. I loaded type

A film, I was still doing that, because I wanted to enhance the color of

dawn. That was where I was lucky. It was first light so it allowed me, it

was the same thing that I had done with the Cheetah, to crank down the

shutter speed and let her rip. I had enough density in the sky so that I

could stop down, and go for 15, 20, 30, 45 second exposures.

Chris/Larry: Are we still talking hand held?

Pete: No, no, Iím on sticks. The volcano was pretty close, I was

using a 50. I went back there, itís on my web site

www.PeteTurner.com

and people should check it out. I went back there and as you can see I

wanted to get the same view. I went to the same house and none of my

lenses would cover that angle. I went to a camera store and said to the

guy, Iím a photographer from the states. Do you have a Nikon camera? He

said yes, I have a real old one. I said what do you got? So he showed me

and it had a 50 on it. I said, can you let me borrow that lens? He said

sure. And I said, well listen, you must want something down, a deposit or

something. I said, hereís an F5. I said Iíll loan you this to look over.

His eyes lit up and I had the same exact lens and I was able to do it. And

I have those Aíd and B/d on my web site. Which also features pictures from

African Journey. Thatís

www.PeteTurner.com.

Chris/Larry: Itís a very nice web site. I think I counted over

130 different images on there that people can come and look at. Itís

beautifully laid out. Do you sell prints off of your site? Is there some

way that people can buy Pete Turner originals?

Pete: You can click on it to order books from Amazon or Graphis

and there is a place that they can call me if theyíre interested in

prints.

Chris/Larry: As far as the whole purpose of your web site. Did

you see the web as a marketing tool or another publications medium? How

did you approach your web site?

Pete: Well, my approach on the web really is to have a presence

on the web that I can refer people to. Itís a resource for people that

want to know about you or what you do. Itís great because itís not like a

magazine that comes and then goes. Itís up for anybody anywhere. And I

realize that. I really havenít tried to use it as a heavy marketing tool

in any way. But itís always there if I want to do that.

Chris/Larry: What kind of equipment are you using now? Youíve

used Nikon all your life.

Pete: I use a Nikon F5 and a complete assortment of lenses.

Chris/Larry: When you go out and when you shoot on a personal

assignment, do you take a large compliment of lenses, or do you carry a

minimal kit?

Pete: I really like the Nikon 14mm, itís a beauty. And I like

the 18Ė35 and 70Ė300 zooms.

Chris/Larry: So you do use zooms as well as fixed focal length

lenses.

Pete: Yeah, I never used to but theyíve gotten so sharp and they

are so light.

Chris/Larry: What about digital cameras? Do you work with the

Nikon D1?

Pete: Yes. I have a Nikon D1. Itís a lot of fun. It saves you

the trouble of scanning.

Chris/Larry: I know you used to be a big Kodachrome shooter and

weíre all grateful that you were because Iím sure a lot of the pictures of

African Journey wouldnít be with us this many years later if you had shot

them on a less permanent media. What films do you shoot today?

Pete: Iíve been shooting Ektachrome VS, and Fuji Velvia but

unfortunately Iíve not been shooting that much Kodachrome.

Chris/Larry: Do you see much difference in the scans you get

from your shots you do on your Kodak and Fujichrome transparency materials

versus the tonalities and colors you would get out of your Nikon D1

camera?

Pete: Oh theyíre different.

Chris/Larry: Is that something you think is a positive

difference? Or do you find that the differences are notÖ

Pete: Theyíre just different. Itís like TV versus film. I donít

know why. I mean, I could be wrong. Remember the old days where theyíd say

oh thatís shot on video and thatís shot on film.

Chris/Larry: And you can see a difference in the tonality or the

dynamic range?

Pete: Thereís different things going on. Like when you go into

adjustments in the curves and levels. Youíre going to go in and do

different things with it in order to get it to where you want it.

Chris/Larry: I remember reading an article that quoted you

saying that you photographed with an optical printer in mind. That was

about 20 years ago. Now that youíre using Photoshop, do you shoot with

Photoshop in mind the way that you were said to have shot with an optical

printer in mind?

Pete: No. I think that PhotoShop is wonderful. I think that the

digital darkroom is great. And there are so many more things that you can

do with it than you could in a conventional darkroom. The only thing that

I have to complain about is that your eyes get tired looking at a monitor.

You know itís one distance all the time. I think everybody could relate to

that. I miss the movement in the dark room youíre actually moving around

and doing stuff. Your digital darkroom is basically your screen, your

keyboard, and your tablet or mouse.

Chris/Larry: Do you do all your own Photoshop work?

Pete: I do most of my retouching and stuff. I work with Autumn

Color with a fellow by the name of Mark Doyle, who is a wonderful digital

artist and helps whenever I have problems. Weíve been printing using Fuji

Crystal Archive.

Chris/Larry: I actually spoke with Mark. He explained about the

Light Jet prints he is producing for you on Fuji Crystal Archive paper,

and that they are really beautiful. Do you have any upcoming shows that

you will be exhibiting them at or any galleries where your original prints

can be seen?

Pete: Not right now. Weíre currently working on gallery

representation. And weíre building an archive of my best work, which is

something that I havenít done for many, many years because when dye

transfers stopped, well thatís a whole other story. You have to pick your

process, and a lot of people are being seduced by the ink jet process. Iím

personally using an Epson 3000, but Iím using it for proofing, because I

still like photographic prints.

Chris/Larry: Iím curious as to your advice that you would give

to young people today. People who are starting and wanting to get into a

photographic career?

Pete: Donít get in the business (Laughs) stay out of the

business. Iím just kidding. I think that photography is a wonderful,

wonderful profession. I do think itís gotten tremendously overcrowded

though. Thereís a lot of schools and everything. It was a lot simpler when

we went to RIT, and itís not as exciting in terms of magazines and outlets

to market your work. So it has to have gotten tougher out there for

people.

Chris/Larry: Would you recommend that people follow a formal

education path of a school like RIT?

Pete: I definitely would. Especially schools like RIT where they

can learn to use the computer and maximize their abilities on it. Going

forward, the camera and the computer are one basically. Theyíll be

spin-off people who might want to do processes like daguerreotypes or

things in the old way. But, thereís no getting around it that digits and

pixels have taken over grain or if they havenít already they certainly

will. They have for a long time in the advertising world where the

separators and processes have been digital for years. There were Hell and

Crossfield scanners way before Photoshop. I used to use them.

Chris/Larry: And now you have it on your desktop. What a

difference. When you are out shooting, you say that you do not create

specifically with Photoshop in mind. Do you still proof on a light box? Do

you still look at the transparencies?

Pete: Thatís the one thing I miss with digital imaging. I like

to handle chromes on a light box. I like to compare exposures and

different colors. I like to look at a roll of film. I like to handle it

and spread it out on a light box. And I like to, if Iím submitting for

something, select things. I like to put them on a real light box, look at

them, group them together. And itís different doing that on your computer.

Does it make any sense to you?

Chris/Larry: Absolutely. You can look at hundreds of slides in a

minute, while reviewing that many on todayís computer equipment can take

much more effort. Sounds more like itís an emotional rush you get from

viewing those transparencies.

Pete: Yeah, itís much more exciting.

Chris/Larry: Are you archiving or digitalizing your film with

archival permanence in mind? Your earlier slides, particularly the stuff

you shot backÖ

Pete: Thatís one of the things Iím doing with Mark. Weíre

scanning and printing and basically building a digital archive of my best

work.

Chris/Larry: And from that archive then you will make prints on

a selective basis for your gallery shows?

Pete: Thatís basically the idea. We actually have a plan. It

took a while to get around to it.

Chris/Larry: Things are changing all the time. The possibilities

that exist today are far different than the ones, when you were working

with a Repronar and were experimenting with saturated colors. You have to

push the limits wherever they are.

Pete: We needed to use the computer because Pete Turner African

Journey contained images that were fading. Given a few more years, some of

them would have been absolutely been useless. We brought them back from

oblivion, from fading oblivion. The things that were shot on high speed

Ektachrome in Africa in í59 were on their last leg.

|

"Can Earring" |

Chris/Larry: I see also that there was a shot in the 70ís of an

Agfa film can in one of the nativeís ear. Was that one of your Agfa film

cans? Were you shooting Agfa back then?Pete: Oh no, these people actually use these things. Their

Masaii, and they actually used to use rocks to enlarge their earlobes, and

the rocks are heavy and uncomfortable. They liked anything hollow that

they can stick in there. Thereís a guy who even has pineapple can stuck in

his ear.

Chris/Larry: Itís a very colorful shot with the pineapple can.

Pete: Yeah. That was his can. It wasnít mine.

Chris/Larry: Iíd always read that you have always been a science

fiction buff and now that we have had our first tourist in space, Dennis

Tito, have you ever had dreams of going to space yourself and creating art

and photographs in outer space?

Pete: Yeah, itís wild. I mean you can just imagine the things

that have to be out there to be seen. Iíve seen these Hubble shots of the

pillars of creation and can only imagine what the rings of Saturn can look

like. Itís very humbling.

Chris/Larry: You certainly would be working with some dark

shadows and some long dynamic ranges.

Pete: The good news is, in the digital world Iíll be able to

transmit data and people will be able to see what is going on.

Chris/Larry: Right. You wonít have to worry about keeping those

300 rolls of film cool when youíre in outer space.

Pete: Just as long as you rotate them a little bit.