Chris/Larry: Lorraine Monk of the

Canadian National

Film Board once said: "You breathe life, love, and happiness into the

art of making pictures." So, which brings you more satisfaction,

creating your own photographs or teaching others?

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: (laughs) I can’t choose between those

because we just finished the second of two back-to-back, weeklong

workshops here recently. Both my teaching partner, André Gallant, and

I were on a total high at the end of each of them, and I think the

students were as well. It was a deeply emotional experience on

Saturday at both of the workshops and just a lot of embracing and a

sense of wonderful support for each other. What I really like to do in the workshops is to encourage

everybody to think of photography as a passport – a medium that provides

the opportunity for exploring one’s creativity.

Chris/Larry: Tell us about your workshops, how do

you make them work so well?

Freeman: Day one, first thing, André and I say

clearly that this workshop is not a competition; we couldn’t care less

about that. If you have a competitive streak in you, then we hope that it

will only be with yourself and that you’ll try to be better tomorrow than

you were today. We don’t care if you’re a beginner. We don’t care if

you’re an advanced professional. It’s immaterial, lets just get to work

here. And so, what happens, quite frankly, is that. I teach as much as I

can about two-dimensional visual design, using photography as the medium

to illustrate everything. Then we turn the students loose - teaching in

the field every day. And we evaluate their work every day, providing the

most constructive suggestions for improvement that we can.

It seems to me that the whole purpose of the workshops is really twofold.

One - to help people make better pictures, and two - to unleash their

creativity to the fullest amount that they possibly can.

Chris/Larry: You've taught a lot of workshops

since you started in 1973.

Freeman: Yes, the same year the Maine

Photographic Workshops started.

Chris/Larry: Do students ask the same

questions now as they did nearly 30 years ago?

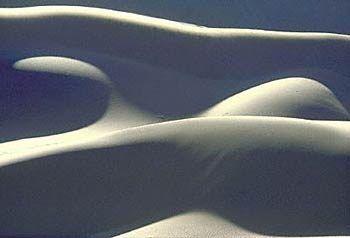

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: To some degree that’s true. But I’ve

changed and my teaching has developed. So, simply because I’m teaching

different things, people are going to ask different questions. For

example, perhaps 20 years ago, I would be teaching use of a wide-angle

lens, something I would never do today. I would come at it from the

standpoint of rendering the third dimension in a two dimensional

image. One approach would involve the use of a wide-angle lens.

But to take another subject, well I’ll give you an example. It’s

better to tell you by way of a story. In the workshops I always give a

short lecture on the subject of texture and it’s expressive potential,

and I often tell about one December morning, back about 1993, when I

looked out on the field behind my house. The grasses had been tall and

very brown, but had been smashed down by snow, and when the snow had

melted, they appeared to be all woven together, integrated. And then a

smattering of snow had come again - so now there were medium, neutral

brown grasses all woven together covered with tiny flakes of white and

little pin pricks of black shadows here and there. When I looked at it

all, I ran for the camera and the tripod and spent about 45 minutes

shooting this tapestry – all the while carefully avoiding any line or

shape that might function as a centre of interest. As I did, I kept

getting higher, and higher, and higher. I was in a state of euphoria by

the time I was finished. So I made some tea, went back out and sat on

the deck and looked at this field and asked myself what’s going on here.

Obviously something significant was going on because you don’t get into

a state of euphoria over shooting some brown grasses with a little snow

on them.

As any good psychologist and many artists would tell you, your art is

always running two to five years ahead of your conscious awareness of

it. So I realized that something was going on that I was probably going

to become aware of. And the longer I looked at that field, the more I

thought that what’s going on here is that I’m looking at an important

symbol of my life at this point. I’ve traveled all over the world. I’ve

been on all the continents. I’ve got wonderful friendships. I’ve had all

kinds of experiences, good, bad, and indifferent. And my life has come

to be a lot like this field. All of these strands are interwoven. All of

the tones are here. The field was functioning as a symbol of where I was

at that point in my life, and photographing it had brought it to my

conscious awareness. That’s why I was on such a high.

Chris/Larry: And you were able to recognize

that.

Freeman: Yes, I was that morning, but when I went

back through my images for a project that came up fairly soon after that

and had to go through thousands and thousands of images, I could see that

the whole thing had started about three years before. I’d started first by

photographing some gravel in my driveway, then another area of found

texture else, and then something else - always concentrating on textures

with no center of interest. No shape, no line that would in any way

detract from the texture. Just looking at the sheer integration of the

thing.

Chris/Larry: It sounds like textures as

symbols of relationships?

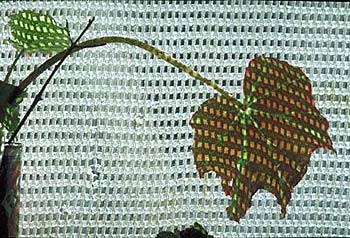

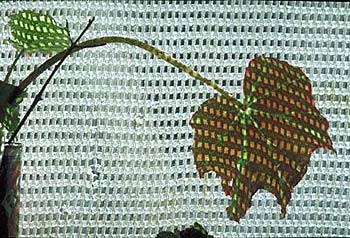

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: Oh, very much so. Because textures are

made up of an infinite number of lines, often crosshatched, or very

fine dots. All of these things, and they’re so ... wonderfully

expressive of a community, of a lot of communal things. There is so

much going on and no one individual or no one thing really stands out

in a texture. Then I started, of course, consciously looking

for textures all over the place and doing more of them. Then I thought that I could create my own. So I got into doing

multiple exposure work. I looked for someone who had done a major body of

work and couldn’t find anyone, so I just set out to learn everything I

could, by myself, about multiple exposures. I spent about three years

really concentrating. It would be nothing to shoot 50 rolls of film trying

different kinds of stuff until I really had a range. Making multiple

exposures with a camera is never an exact science, but I became very good

at predicting what I was going to get. Then that in turn led me to other

things. The point I want to make here is that I’m very unlikely to start

saying, “OK, let’s learn how to make multiple exposures,” or to encourage

students to learn techniques just because the techniques exist. I try

illustrating that the movement towards a technique comes out of

experience, and out of need, and out of desire. That way your photography

will become your experience; you’ll make strides in that way. That the

technique is not something you can just say, oh, never done this. Gonna

try it. Of course you can do that, but it’s more meaningful when it comes

out of your personal experience.

Chris/Larry: Your graduate degree is actually

a Master of Divinity. Can you tell us a little bit about your master's

thesis? I believe it was titled "Still Photography as a Medium of

Religious Expression."

Freeman: I won a Rockefeller

Fellowship, and was allowed to go to a seminary of my choice so I picked

one of the three really good ones at the time, Union Seminary at Columbia.

That was really quite a phenomenal experience. The Rockefeller Fellowships

were for students in arts, sciences, business, who were not contemplating

parish ministry, but would be willing to take a look at it, with no

obligation. So anyway, I was nominated for one of these and received it,

and did the three years, got the degree and decided against the ministry.

But it was an extremely good experience, both in terms of academics, which

were very high-powered, and in terms of the community experience because

of both the professors and my fellow class mates.

In my undergraduate work, I'd gone to Yugoslavia on a scholarship one

summer and took a camera with me. That was really my first camera. I

shot a roll in it before I left and it was working fine, but it was not

working when I was overseas. I came back and I had lost my entire

shooting for the summer. But, on the other hand, I had fallen in love

with photography. So I kept it up in my senior year in the university

and when I went to the seminary in my second and third years.

I was teaching part time at a Quaker school in Brooklyn, just to

augment my funds. Two of my fellow teachers were keen photographers and

they had invited me along to meet their teacher, Dr. Helen Manzer. Then

I subsequently took a ten-week workshop from her. That’s ten evening

classes! And then two more workshops of ten evenings and I really became

totally turned on. And so those things were happening at precisely the

time I had to do a masters thesis, so I thought why not combine the

photography which I’m loving so much with the thesis work.

Chris/Larry: Then you began doing editorial

and advertising work. Do you still take on assignments, or shoot for

stock?

Freeman: I shoot for stock, but not

aggressively. I’m doing very few assignments now, almost none. I

eventually realized that, while I did assignments for a good number of

years, the client really “called the shots.” All this time I stayed in

very close touch with the amateur photographic community and did a lot of

instruction for it. People kept telling me that I should hold workshops,

so I finally woke up to the fact that I had a market.

Chris/Larry: It seems like you were

gearing yourself for teaching right from the start.

Freeman: In a way, yes. I like

teaching. I like it a lot especially the intercommunication with people.

And, I think the teacher is the person who learns the most. As time has

gone by, I have actually been teaching less “photography” and have been

really putting the emphasis on visual design - particularly

two-dimensional visual design.

Chris/Larry: What about the equipment? In

particular, are you finding any students bringing digital cameras to the

workshops?

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: No, although many of them have digital

cameras. We’re just sort of biding our time in terms of when we switch

to doing everything digitally at the workshops. It’s just a little

difficult at this point because we’re limited – quite deliberately. We

have one class going at a time with 15 students. So everyone at this

point is using single lens reflexes. I know perfectly well that

everyone will be switching to digital, probably in three or four

years. For a while there’ll be a number of digital workshops and a number

of non-digital. But, in my view, it’s merely a matter of time until

everything will be digital.

Chris/Larry: Can you tell us about how you

came to co-found the Namaqualand Photographic Workshops in Africa?

Freeman: I was in Africa a few times

between 1967 and 1980. But in 1980 I went to Namaqualand, in South Africa,

which was at that time fairly remote and inaccessible. All I knew was that

they had, from what I’d been told, the most spectacular annual display of

spring wildflowers anywhere on the planet; even surpassing Western

Australia. So I went, although I was a little late, in fact quite late,

because the plants bloom in August and September and that year early

spring came early and I arrived in mid September when the season was

nearly over.

I was in this quite remote area and I had no place to stay for the

night, so, I went back to a little village and it had a little tiny

hotel with nine rooms. So I got one of the rooms. And that night the

woman who ran the hotel with her husband, Colla Swart, put on a slide

show. Now, she had never put on a slide show in her life before, but she

had some other guests who she was putting it on for. So I asked her, can

I watch her slide show? Now she was speaking in Afrikaans, which I did

not speak at the time. She said to me in English, “I’m going to talk in

Afrikaans,” and I said “OK, I just want to see the slides.” Well,

although the slides were utterly god-awful, the subject matter just blew

my mind.

I had a copy of my second book, “Photography and the Art of Seeing,”

in my suitcase, so I went and got it after the show and gave it to her,

but I did not tell her that I had written the book. I just said here’s a

book that may help you with your photography, and went to bed.

Anyway, the next morning I’m eating breakfast and she comes charging in

and says “I’ve got a bone to pick with you.” And I said, “what did I do?”

And she said, “you’re a professional photographer and you sat through my

slide show last night and I am mortified.” And I said, “no problem, what’s

going on?” And she said, “look, I read that book with a torch, a

flashlight, until 2:00 in the morning and suddenly it dawned on me that

your name was not only on the front of the book, it was in the hotel

register. And so, I realized you had written the book.”

And I said, “okay, lets make a deal here, I’d like to see some flowers.

Can you show me some?” She replied, “look, I’ll take two days off work

(she had about four jobs) and you’ll teach me everything you can about

photography and I’ll show you the best flowers we have left this year.”

Well, that was the beginning of a long and fast friendship. Colla is now

an extremely experienced and talented photographer.

We founded the workshop three years later and there were three students

in one class and two in the other. Photographic workshops were totally

unknown in Southern Africa. But gradually we built and now we’re running

about eight or nine workshops and people come from around Africa and

various parts of the world. I don’t teach them all anymore; she and I used

to do them all together. She is involved in all of them, and I am involved

in some of them each year. I’ve now made 27 extended trips to Africa and

number 28 is coming up this year. I’ll be going for most of August and all

of September, which spans much of the peak flower season..

Chris/Larry: That's a great story. Do most of

your trips to Africa coincide with the peak flower season?

©Freeman Patterson

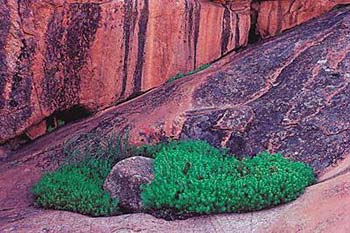

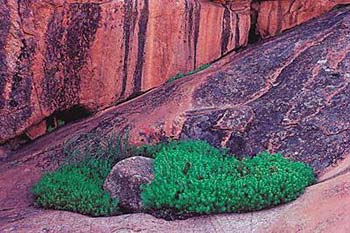

Freeman: Most of them do, but by no means

all. We’ve started running workshops in the off-season as well, and

this year, for the first time André will be teaching there as well –

in March and April. The so-called off-season workshops make sense

because the area, the northwest corner of South Africa, is very

desert-like, but not just dunes. There are plenty of those to the

north. But it’s a rocky desert; it’s a mountain desert, which I think

is spectacular. The mountains are extremely old and they’re crumbling

and so there are great piles of boulders, I mean boulders ten, twenty,

thirty, forty stories high stacked on top of one another – great round

boulders – it’s just incredible.

Chris/Larry: You've told us a bit about how

you respond to things, how you go out and photograph. But how do you

instruct your students, all these people with different perspectives?

How do you help them to go find pictures? Can you talk about the state

of mind, how you approach your subject? How you recommend they approach

subjects or learn to see?

Freeman: Well, basically we'll say look, you

can't go out and find pictures. Don't wait for the state department of

tourism's sign "Scenic spot ahead" or something like that. The

best place in the world to make pictures is where you are standing at

the moment. Let's start right here.

For example, wherever I'm talking to a group of students, I'll say

give me a number between 1 and 30 and one of them will say 17. And I'll

say point me in a direction, and they'll point me in some direction. So

I'll walk 17 steps in that direction put the tripod down and make 10

really credible, good images without moving the tripod. And usually I

can do so without swinging the tripod or the camera on the tripod more

than 45 degrees. I could keep going and shoot the whole roll without

moving it.

You know there is a tendency on everyone's part, my own included, to

wander in search of things and fail to realize that the pictures come

only half from the outside; the other half comes from you. You'll just

never really develop if you go around looking for pictures to take. In

fact, I never use the words "taking pictures;" I always use

the term "making pictures."

Chris/Larry: It would seem you have touched

on the difference between looking and seeing.

Freeman: Well yes, for sure. If I see

somebody wandering the field, I’ll say “Come on, let’s just let’s stop

right where you are, let’s get the tripod, whatever height it is, leave it

there, let’s work right here.” At first they’ll say “well there’s nothing

here” and I’ll say “Oh wow, um, you know, the most significant place in

the entire world at this moment is this spot. Everyone else isn’t here,

it’s exotic to everybody else, so don’t think it’s poor by comparison to

any other place.’

My teacher partner and I often say that if we could

not leave the classroom, we could do the workshop. We could give you the

fieldwork. We could run the whole week in that room and have all kinds of

exciting images.

We give assignments on Thursday night, that workshop participants shoot

on Friday morning. Each person gets a different assignment, based on

careful observation of our students.

I’ll just give you a few examples: one person might be given a white

sheet and asked to photograph it as a landscape; somebody else might be

given the topic “outer space.” We don’t care how they deal with it.

Someone else might be given a colorful shirt and told to photograph it,

but only in water. One of my favorite assignments, and I’ve only given

it two or three times, is the Joseph Campbell quote, “the privilege of a

lifetime is being who you are.” We gave it to a guy this week from near

Chicago and it was just one of those intuitive things. We could tell

this guy was experiencing a period of real personal liberation, and he

really carried that assignment off; it was beautiful to see what he did.

Chris/Larry: So you're using your own

judgment, working with your students to intuitively know what

assignments may get them really seeing and working with things in a new

way.

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: Yes. For example, this is another case

of intuition: we gave a woman at our workshop this year a pile of

junk; just old car parts and stuff like that. What we do is ask each

person to put together a slide essay of 15 to 25 slides from the

shooting, just one slide after another. They can play music, they can

talk or they can sing or dance; whatever they want with the slides.

But, basically it has to be a simple presentation of what they

consider their best 15 to 25 images.

Anyway, we gave this woman the junk pile. She had been photographing

incredible wild flowers and spider’s webs and beautiful things all week.

We didn’t know until Saturday morning when she presented her essay,

until she stood up, how furious she was when she got this assignment.

She said “I really lost it. And I made clear to all the other people in

the workshop that I’d lost it.” And they said, “well, we’re doing our

assignments and you’re gonna have to do yours.”

So, she said, “I went out and did it and I hated it at first.” Then

she said, “the more I started working in the junk, the more I started to

see beauty in it.” “Now,” she said, “the reason I didn’t want that

assignment is that my life at this point is full of junk, my marriage is

on the rocks. I’m going back home to face all kinds of crap. The last

thing I wanted was an assignment that even reminded me of junk.’ And

then she added, “what happened when I was photographing is that I turned

it into a beautiful experience, and I see the parallel, and I’m going

home with a totally different attitude.” So there you go. You don’t

really know. But if you work closely with people, sometimes you intuit

correctly. I mean she had everyone practically crying when her

presentation was over and lots of people got out of their chairs and

went over and hugged her.

Chris/Larry: And she was able to make the

connection that the creation was more than just making the picture, that

the creation involved all aspects of her life.

Freeman: Absolutely.

Chris/Larry: Now, when you create

images, do you ever think about how those images will be presented or

seen? In other words, if you shoot an image, do you think about how it

might end up as a photographic print as compared to, say, an image in a

book?

Freeman: I never think of it. Never. I

just photograph for the sheer joy; like for example, today, I didn’t think

I was going to be doing anything. I photograph nearly every day, but today

was super busy. I had a doctor’s appointment, a checkup before I go off on

this trip, and then as I’m crossing a bridge I was stunned by the scene

and yelled “Oh my God.” So the minute the appointment was over I charged

back to the bridge and shot a couple of rolls.

I almost invariably have my camera and a tripod with me. That is how

I do almost all of my photography now. It allows for pure response to

the subject matter and whatever is going on inside of me. Then I use it

for teaching, I use it for books, I use it for print, and a certain

amount I use for stock, but I don’t shoot with that in mind really.

Chris/Larry: Are you a purist in terms of

what you see? Do you feel comfortable, say, moving a leaf to improve a

composition, or maybe revisiting it in Photoshop later to eliminate

something?

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: Well that depends on the kind of image

one I’m making. For example, if I’m doing documentary photography of

any sort, then I try to be honest and not deliberately falsify the

truth of the situation, certainly. But then there are all kinds of

images when the real truth is not a literal one. The real truth you

are trying to express is something that proceeds from you, and the

subject matter that you are using is like a sculptor’s clay.

If you take sculpture, for example, you have people who sculpt

realistic images of say, people. They make a realistic bust of Winston

Churchill or Franklin Roosevelt or something like that. That’s one

approach. But take the sculptor Henry Moore, for example. So many of his

sculptures, women especially, have these enormous buttocks. When he was

a kid, when he was like two or three years old, his mother was in bed a

lot. And he used to come by the bed to talk to her of course. And here’s

his mum in bed and what does he see but her bum sticking up in the air.

And he’d reach up and touch his mom. As an adult he’s sculpting and he’s

reliving something of himself as a child. Maybe he’s using a model, but

perhaps he makes her bum a lot bigger than her real bum was. Now, is he

falsifying something? Not in my opinion. He’s really being honest with

himself.

Chris/Larry: And obviously, there are many

other people who have enough of a synergy or a resonance with his vision

that he was able to communicate very clearly to a lot of people.

Your images have resonated with many people. I clearly remember an

exhibition of your work at Expo 67 in Montreal. Were you surprised by

the public's reaction to your images in that particular venue?

Freeman: Well that was an exhibition

of a book called “Canada: A Year of the Land.” It was our centennial year

and I had 55 pictures in that book. And the shock was getting them in the

book in the first place. If you go back to 1967 and consider the Canadian

market versus the American market in terms of population, that book sold

over a million copies, which was phenomenal by anybody’s standards.

Chris/Larry: I know that I was one of the

million people who bought it. I was very impressed with it myself.

Freeman: I was living in Toronto at

the time; my postman knocked on the door one day and he said, “I just

bought this book ‘Canada: A Year of the Land;’ by any chance are you the

photographer?” And I said “yeah, you got the guy.” Then another day I was

flying outside of Quebec city and I was taking pictures from a Cessna and

the pilot said, “you know that I’ve got 9 kids,” and he said, “my wife and

I decided we were going to buy a copy of that book as a family birthday

present for this special year.” Little incidents like that made me feel

great.

Chris/Larry: Let talk a bit about equipment.

I know that you don't emphasize equipment, but I'm curious. You say you

shoot everyday. Do you always carry a camera with you; what kind of kit

do you normally travel with?

Freeman: I don’t always have a camera

actually on me, but I have one within easy reach. Even though I travel

quite regularly, for example, I’ve just come back from England and

Scotland and Africa this year, I travel very light. I have a light ART 190

Manfrotto tripod (that would be a Bogen in the U.S.), with a press type

head. I normally carry three camera bodies, all 35mm; one will not be

used, it’s merely a spare. I would carry a shorten zoom like a 24 to 50mm

and maybe a 70 to 300mm zoom and a macro maybe.

Chris/Larry: What brand of equipment are you

currently using?

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: You know I don't normally answer

that question. I just say 35mm (laughs). I'll tell you why. I've been

using pretty much the same two brands; one I've used since 1972. I'm not

saying they are better than any other. I don't care if it's Pentax or

Nikon or Canon or Minolta or Olympus. As far as I'm concerned, take your

pick.

Chris/Larry: So it's pretty clear that you

believe that the choice of equipment is not critical to a photographer's

vision.

Freeman: Not at all.

Chris/Larry: Have you experimented with any

digital cameras?

Freeman: I haven’t. And quite frankly,

because I sell quite a lot of very large prints, up to 32 by 48, I’m

waiting for is just a touch more quality and a little less price. It

doesn’t mean a thing to me to be first out of the gate, leading the pack

on this one. I’ll switch to digital when I think it is smart for me to,

when everything is right.

Chris/Larry: Do you digitalize your pictures

so they can be worked on in Photoshop?

Freeman: I haven’t been doing much

myself. But for the last four years I’ve only been printing giclee prints,

and I mean the real giclee prints with dyes. For my own exhibitions and

for my own hanging, I’m using the Somerset Velvet paper, which has a

pretty high rag content. Then those are flush mounted and laminated to

about a ½ or ¾ inch board which is painted black around the edges, and

then a spacer is added at the back so the pictures stand out from the wall

a bit. There’s no glass, just the laminate; it’s as dull as the print

itself and you hardly know it’s there at all. But it allows me to wipe the

prints if they get dirty.

Chris/Larry: In that process, how helpful has

Photoshop been in creating and helping you make images that reflect your

way of seeing?

Freeman: Well, I don’t see Photoshop,

in theory, as being any different from working in the darkroom. I’ve

mainly been using it just for corrections or enhancements. Lets take a

case of one print of an old abandoned house with an absolutely wild wall

and an old rusted bedstead right against it. Now the image worked

beautifully in the slide, but I knew in the print the reddish rust in

major parts of that bedstead had to be enhanced. So it was. That’s the

kind of thing at this point I’m more likely to do - or to remove

something. I’m doing virtually all my manipulative, interpreted stuff in

camera at this point. Which is not to say I will always be doing that. In

other words, I think digital processes probably will be far more useful to

me in the future than they have been.

Chris/Larry: Do you personally do the

Photoshop work or do you work with other people who are expert in

Photoshop?

Freeman: No, mostly I'm working with other

people. By the way, learning Photoshop is one of my projects for this

winter. I have a really good teacher and I'm hoping to make use of it

this winter.

Chris/Larry: It's a deep program. You can

spend a lot of time playing with it. Freeman: You know, I have a problem with

that. It’s the same problem I have with the darkroom. I like to be

shooting and I don’t like sitting on my ass behind a computer for very

long periods of time. I will never climb Mt. Everest, but I am definitely

an outdoor man.

Chris/Larry: Tell us about where you live.

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: Well, I live on an ecological reserve.

This is mostly land that I owned until quite recently; it’s about 272

acres and it’s surrounded on three sides by water, and it’s extremely

beautiful. The part I didn’t own I knew was slated for development. So

I said to the Nature Conservancy of Canada, if you can get that other

piece of property, I will donate mine. And they were able to buy it

and so I donated all of mine in return for a life’s lease. So I am

surrounded by nature.

I don’t want to sound maudlin when I say this

and I don’t want to sound sweet and gooey and all that kind of thing, but

my connection with the natural world is really important. It is my primary

source of spiritual well being. I find myself very emotionally connected

with plants and I have difficulty in the winter quite often when the snow

is deep, because plants, with the exception of trees, are covered up. I

don’t care if the grass is brown, but I like to see it and other plants as

well, even in their dormant state. And I’m photographing less when it’s

snowing than any other time of year. And it’s not just because snow makes

it more difficult to get around, but it’s because of the life process that

I love seem to be absent, I guess. Spring is my very favorite time of

year. I really emotionally feel that everything that is good is possible

in the spring..

I try to arrange my springs to get in more than one. One year I managed

five. I started in Mexico, then went to the southern United States, came

to New Brunswick, went to South Africa, and then went to New Zealand for

the fifth (laughs). And they ran from February to November. And the fact

that I had lived through one didn’t make the next any less inspiring, any

less emotionally strong.

Chris/Larry: Lets talk for a minute about

your books. So far you've done six large-scale art books, and written

five best selling instructional books. In your latest book, "Photo

Impressionism and the Subjective Image," you talk about the classic

documentary tradition versus the altered reality of the impressionistic

tradition. Can you elaborate a little more about that?

Freeman: It seems to me that these

really are the two great traditions of the photographic medium. For a long

while, the documentary tradition was the more significant, the more

common. I think, in a way, it still is with the average person who has a

camera to take pictures of their children, and family events, and

activities, and things like that. Essentially all these pictures are

documentary.

My previous book, “Odysseys,” is extremely documentary, as

far as the images are concerned. Everything you see is as I saw it. But I

obviously tried to use certain lighting, certain design, or something.

Each image was of a particular point of view at a particular time of day.

But maybe most people would not be so careful to see a

scene in those ways. Maybe that’s what makes a serious photographer

different from the average person.

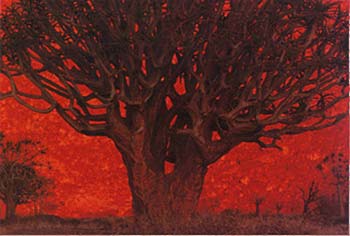

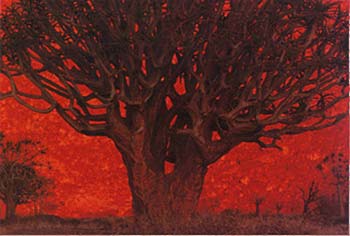

On the other hand, photo impressionism makes no attempt at literal

reality. For example, take a multiple exposure of a tree, 16 exposures

of the tree bending over. It’s a black skeleton of a tree with blue sky

and white clouds behind it. When you look at this picture, there’s a

sense that the tree has bent an enormous degree. It’s bent way over and

maybe snapped back. In other words, what I’m doing here is simply

treating trees as metaphors for human experience, which they are very

much for me. You know, if you can’t bend in the wind, in the storms, if

you can’t bend, you’re going to break. And that’s as true of trees as it

is of human beings. And it’s the people who can bend, can ultimately

snap back who can survive emotionally. It’s not a literal description of

a tree, but I hope it’s an honest metaphor.

Chris/Larry: So is there then a visual

language of impressionism, or is that entirely in the mind of the

perceiver?

Freeman: I think it’s primarily in the

mind of the perceiver. But, if you come to that photograph of mine, you

don’t know what my metaphor is. You come with your life experiences, and

you may immediately connect with my metaphor, or you may not. You may just

look at the image and say, “hey, I really, really love that photograph of

the tree. It’s just so alive and dancing and so on….” And you may like it

for primarily visual reasons, and that’s OK with me. Or you may hate it,

and that’s OK with me too. But I hope you won’t ask “what is it?”

©Freeman Patterson

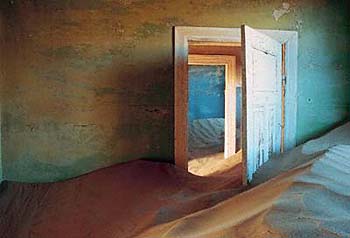

Chris/Larry: In your book Odysseys, you've

talked about the image of the bed with the painted wall behind it. The

images you have on your web site from that book are spectacular. Would

you consider them to be more in the documentary tradition?

Freeman: Very much so.

Chris/Larry: Rather than the impressionistic

tradition?

Freeman: Yes. Even though some of them come

across as impressionistic. They are authentic renditions of what I saw.

Chris/Larry: Where were the wild buildings

with the incredible walls and the sand flowing through the rooms?

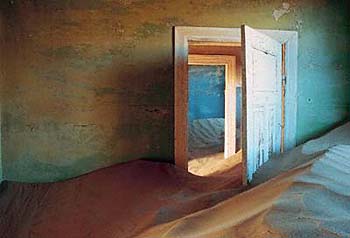

Freeman: There are four abandoned

diamond-mining towns in the southern Namib Desert, in the country of

Namibia in Africa. They were all abandoned about 60 years ago because of

changes in the way diamonds were harvested. So the big diamond companies

closed the towns, told workers to take what they wanted and leave. Also,

it was difficult to supply people in there – especially with water..

Some of these towns even had clubs, hospitals and recreation centers.

Three of the four towns, after 60 years, are still off limits to the

public. It took me about nine years from the time I heard about them

until the time I got permission from De Beers to go in. It was a matter

of making connections.

I went to the towns in ‘94 and I went back again in ’96, both times for

12 days, and both times with five other people. The second time I was in,

the other five people, who were also photographers and geologists, were

all more interested in the desert, which I was also extremely interested

in, but I’d done an awful lot of work on deserts and I just said,

“Freeman, you’ve got to stay with these towns.” So the second time, I

literally was alone in these towns for 12 days; all by myself I wandered

these ghost towns. Let me tell you, it was an experience I’ll remember

‘til I die.

Chris/Larry: You've done wonderful work with

it. They're very striking images. The surreal juxtaposition of sand,

doorways, wall paintings and other artifacts, to my eye, are more in the

impressionistic mode than the documentary. But I guess it's in the mind

of the perceiver…

Freeman: Well I think a thing can be

both. There’s no absolute distinction - in a sense the distinctions are

just sort of working handles. But sure; that picture with the bed, when I

came across that situation, I remember I just had a gut reaction, an

intake of breath. Oh my God! And then you know I photographed it in some

different ways. But, it is highly impressionistic in a sense, yet a lot of

that impressionism comes from the sand blasting. The wind has been blowing

sand through that room and it’s blasted the paint, and the salt spray from

the fog coming in from the ocean helped erode the bed and rusted it. In a

way, I’m just documenting the impressionism that nature has created.

Chris/Larry: I know many people who have done

impressionistic work, people who are interested in abstracting things.

But it's all too easy to abstract something in a clichéd way. For

example, the classic shower glass approach to impressionism where

everything gets a similar blurriness. How do you avoid the clichés when

you're working with something as flexible or as open as an

impressionistic approach to photography?

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: (laughs) I'm not sure I do avoid the

clichés. But one edits and makes a judgment. At least I find I try all

sorts of things and sometimes afterwards I think, well, you've been

there before. Other people have been there before. Is that fresh or not?

But it still may be worth doing. I'll just step back here a little bit.

I would personally make a distinction between abstracting and

non-representational work.

For me, the first step in making a picture, or at least composing a

picture, is to abstract. In other words, what lines or what shapes am I

dealing with? Look at a landscape, a common subject or theme. It could

be a vast field of flowers or a forest and river. Almost invariably,

there’s hardly an exception, I can abstract the fundamental design of

it. I can see three rectangles, for example, or three triangles, or

whatever, within the viewfinder. It’s a very unusual composition that

has more than six shapes. Two, three or four are the most common.

So, I’m always asking, what visual building blocks am I dealing with

here? I’m peeling labels off. I’m abstracting. The thing that you’re

talking about, blurring, or things like that; those I call

non-representational. It’s about not representing the object in the

sense that the object represents itself, but about representing

something else.

So, abstracting for me is just something I do as a matter of course.

Whether or not I then treat the design that I see there in a

non-representational way is another matter.

Just to clear up this business of what I mean by abstraction, I

sometimes use the example of making a stew. If you’re going make a stew,

you need to abstract or get below food labels and ask what the main

ingredients or building blocks of the stew are? They are, presumably,

meat, vegetables, and liquid. Having abstracted or determined the building

blocks of stew, you can then make specific choices intelligently. You can

choose beef or lamb (for the meat); onions, potatoes, parsnips and carrots

(for the vegetables); and a bit of water and red wine (for the liquid).

OK, a stew is made up of three main building blocks. A picture is also

made up, perhaps, of three – shape, line, and texture. You look at both

challenges and ask what you are going to do? “Am I going to make a nice

realistic stew, where the beef really tastes like beef? Or am I going to

do something else with it?” The same goes with the visual ingredients of a

photograph. What will you do with the shapes (two important triangles and

a circle, perhaps) and the three oblique lines? Will you emphasize or

de-emphasize the texture by the direction of the lighting?

Chris/Larry: And it's actually the

relationship of those components, the tension and balance between them,

that, in the case of a stew, causes the flavor to be really exciting and

interesting, or perhaps overwhelming, or even going off in a direction

you don't want it to.

Freeman: That's right, right on.

©Freeman Patterson

Chris/Larry: So, when you're working with

your shapes, it's one thing to abstract them, but what part of them lets

you know the relationship that should exist between them? In other

words, you may see this as a triangle and that is a square, or a line.

At what level are you deciding how those shapes should relate as an

image, or is it intuitive?

Freeman: Well, I think it becomes

intuitive. Let’s take another example here. Let’s think of the design of

language. Instead of beginning with light, we’re beginning with sound, and

when we’re young we begin with funny little noises, then we begin to form

the sounds into words, and then we string them together into phrases and

clauses and sentences. And then, when we go to school, we learn that the

words that we’ve been stringing together have different names. Some are

called nouns, and some are called verbs and some are called adjectives.

And these are the basic building blocks of speech or language. And then,

we also learn that if we rearrange nouns and verbs and adverbs and

adjectives in a sentence, we can alter the meaning or the nuance of the

sentence. So we get so good at speaking that we do these things

automatically. When I’m talking I can speak a sentence flat – no emphasis

on any particular word. I may say “I must go now.” Now, let’s speak it

again, “I must go now.” It implies, with the emphasis on the word “I,”

that other people have gone ahead of me, but now it’s my turn. Or I can

emphasize the “must,” or I can emphasize the “go,” or I can emphasize the

“now.” All of those words having more color added to them; i.e. more

emphasis in my spoken language changes the meaning of the sentence, or how

people really understand it to be. So what I’m saying about the visual

design is that you have to learn until it is second nature. This is a

life-long challenge.

Chris/Larry: Is that how you teach your

workshops?

Freeman: Yes. In other words, I say to

all of the participants, I’m not interested in teaching visual design for

the sake of visual design. But you should be learning it because it

enables you to do two things. When you know how to design images well you

will be able: a/ to communicate information accurately, in other words,

documentary stuff, and b/ to express your feelings clearly. And, it seems

to me, the better you can handle visual design, the better you can

communicate information and the expression of feelings through the

medium of photography . So for me, the craft of visual design can

never be fully learned, but you can get better and better at it like

learning how to drive a car.

Right now the autumn color here is spectacular; all kinds of people

are going out for a drive, and they’re not thinking about what they’re

doing, just having a great drive. However, by God, when they come up to

a green light and start to go through it and someone crosses in front of

them, they know enough to snap back into the left-brain and hit the

brakes. It’s automatic. And that’s how design should be for all

photographers. And it doesn’t make any difference if you’re Cartier

Bresson or Ernst Haas. Both were masters of visual design, but they were

totally different photographers.

Chris/Larry: If I can get back to the

concept of the building blocks. When people go to school and they’re

taught that this is the noun and this is the verb, they diagram a

sentence. Do you, in your workshops, show them in their pictures that

these are the shapes and these are the relationships? Do you also diagram

a picture in that way for people?

Freeman: Oh yeah. I’ll often break

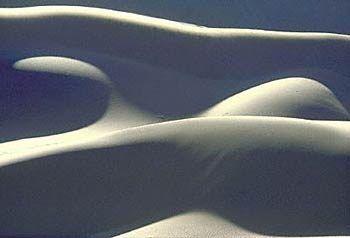

down my pictures. For example, two pictures come to mind. Think of blue

sky and think of sand. It just happens that the horizon is pretty much a

straight edge, OK. And I’ve divided the picture into halves. So it’s half

blue sky and half brown sand. Now let’s pretend I tilt the camera up, so

there’s more blue sky and less sand. It’s still two shapes, that’s all it

is, two rectangles in the picture. Everybody sees this; it’s pretty

obvious. Now I say that I’m going to change the subject matter completely,

but retain the composition. The next picture is a vast field of flowers. I

mean kilometers of flowers, just going on and on. The texture is very

complex, but it’s two rectangles of the same size and placement as the

first composition. In the upper rectangle, the bulk of the flowers are

mauve sprinkled with pinks. In the lower rectangle, the narrower one at

the bottom, they’re mostly oranges. Then I point out again that it’s the

same composition, but different subject matter - the same two shapes, but

the content of those shapes is utterly changed. I’m constantly doing that.

In the lectures I always talk the very first day about tonal contrast

and color contrast and how they allow us to see the visual building

blocks. And then I talk about line, shape, texture and perspective. And

then, on subsequent days, I talk about arranging these building blocks

according to principles such as balance, rhythm, proportion, dominance,

and so on. In other words, what are the visual building blocks of

two-dimensional design, and what are some of the ways to arrange them?

And I always stress that there are no rules. I’m trying to give good,

solid information that anybody can use in all kinds of situations. In

fact, I only have one rule. That is never process your film in mushroom

soup, because it doesn’t work.

©Freeman Patterson

Chris/Larry: That is a way of analytically

reviewing what's there. Earlier in our interview you spoke about the

relationships, the perception of metaphors and such. Is that a different

part of the brain that forms the metaphors?

Freeman: Well, no. Visual design is like

language; we have to know how to speak and to write if we're going to

convey ideas in language. So we have to know linguistic design. All I'm

saying is that with photographs we have to know pictorial design. We

have to know it well if we're going to show either documentary or

impressionistic pictures effectively, if we're going to create them.

Chris/Larry: Speaking to you actually reminds

me of the teachers I liked the best when I was in school. They were the

one's that taught me how to learn. But it's very rare that you find a

teacher that inspires you to go out and learn. And gives you the tools

that you need to learn. That's what I feel that you do within your

workshops to your participants.

Freeman: Well that’s what I certainly

try to do. And I want to provide people with the tools. Photography is the

medium, design really is the craft, but each of us is a different

individual. So we have a common medium and we have a common craft, but how

we use both the medium and the craft will depend on our own personal life

experiences, and our genes, and a whole bunch of other things, which for

me is very beautiful.

I find that people who teach design in a rule-oriented way, or who

have rules for composition, are simply saying, “look, it’s already been

done, so your imagination, your input isn’t important. Forget about

being imaginative. Sticking with formulas is the death of the individual

as far as I’m concerned.

Chris/Larry: Speaking of your workshops;

perhaps looking toward the future. Do you see at anytime in the future

that you might put your workshops on the Internet, on the web?

Freeman: Do you mean the content of them?

Chris/Larry: Or even the interactivity. Where

people would submit pictures and you would critique them.

Freeman: I don’t think so; I’ll tell

you why. We’ve kept the operation small, and it’s quite deliberate. It’s a

very rudimentary lodge with a dining room and a teaching room with light

boards in it. And there are five two and three bedroom cottages, log

cabins in the woods with a beautiful view. There are no television sets or

radios. We have film pickup and film return every day.

There are 15 people plus myself, my teaching partner, and another

field instructor. That means when we’re in the field, there’s one

instructor to five participants. We also rotate among the participants

daily so every field instructor gets to work with every participant. We

also have an optional early morning breakfast. In the summer, breakfast

is available at 4:30 and there’s an optional field trip that leaves at

5:00 a.m. in the spring and early summer and a regular instructional

trip later. Just five people with one instructor.

I think what the web would be missing is the kind of communal

experience that a workshop like ours has. We live together, eat together,

and photograph together. And yet if you want to be alone, you can be alone

any time you want to be.

You can learn a heck of a lot from the thing you’re suggesting, sort of

a web workshop. There’s no question. But whether you can get the intense

human contact where human beings touch each other in important ways, I

don’t know. And remember, I already mentioned that I don’t like to be

sitting on my butt in front of a computer for long periods.

Having said all of this, I hasten to point out that I have put a great

deal of workshop content and attitudes into my instructional books. This

is especially true of Photographing The World Around You, which is based

directly on the workshops, and also Photography and The Art Of Seeing,

which really conveys the attitude and approaches of the workshops.

Chris/Larry: So you immerse people in an

experience and use the social interaction to forge and hone the person's

skills.

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: We had one student last year that made

sure his camera strap was really well fastened. And he had a very long

cable release. Then he started twirling his camera around him; he just

kept spinning, making multiple exposures. That’s the extreme. I don’t

know how many of his resulting images were any good, but the thing

that mattered was that he learned from the exercise. He looked at all his

pictures and said, “there’s a few things I know that I can do. I can apply

this and that” … you know. He got so charged up by the bits that he had

learned, that he got everyone else charged up doing things that they would

not normally do.

Another case in point, and for me this is really funny. We had one

woman, who came with an old camera with just a 50mm lens, nothing more.

She had no close-up equipment of any kind. On day four she came in with

stunning close-ups of back-lighted spider webs with water drops on them,

and I mean close-ups, and they were just fabulous. The whole class

said,”God Jane, how did you do that?” And I said, “Jane don’t answer,

because they’re asking the wrong question; everyone, you’re asking the

wrong question. Appreciate her photographs. Are they good photographs or

not good photographs? The hell with the equipment for the moment.”

So afterwards I told her, “Jane, tomorrow we’ll tell them.” The next

day she came in with more photographs done the same way and people were

going bananas. So I said, ‘OK Jane, you can tell us all today how you’re

making all these images.” “Look,” she replied, “I don’t have any of this

sophisticated equipment like everyone else does in the workshop. I don’t

have a macro lens or anything. But, because I wanted to get pictures of

these wonderful spiders webs close-up, I just went to one of the light

boards and grabbed one of the loupes that we use to look at our slides

with and held it up in front of my lens as a magnifier.”

Chris/Larry: I was thinking she might have

used her glasses. The point is, she had a goal and she managed to

accomplish it. She learned how to solve a problem.

Freeman: That's right. And that was a great

inspiration to everyone else in the workshop.

Chris/Larry: Lets talk about your web site:

http://FreemanPatterson.com. You have some great examples of your work

there for people to view and to buy. You have information on your

lectures and your workshops and such. Have you found the web to be an

effective communication tool for you? Have you been pleased with the

response?

©Freeman Patterson

Freeman: Yes, it has been. I have been pleased

with it. Both for book sales and print sales, but particularly for

book sales. And a lot of workshop inquiries too. I think the thing I

like about it, as far as workshops are concerned, is that by

advertising them on the web we tend to get a much more diverse group

of people, and that’s nice.

We maintain an actual mailing list of about a thousand. We get a

thousand brochures printed every year and we’re always sold out with a

huge waiting list. In other words, if you contacted me and said to put

me on your workshop list I would do that, and you would get a brochure

for the next three years. If we didn’t hear from you within that time, you would be dropped and

you would have to request again. But what’s happening is that about a third of the people have taken

more than one workshop, maybe closer to 50%. Some have taken six, seven

and eight.

Chris/Larry: And do you find that the people

come from all over the world?

Freeman: Yes. For the past two years we've

had people come from Western Australia, the Philippines, Germany,

Israel, South Africa, Ireland. But the bulk comes from the United States

and Canada.

Chris/Larry: You've spoken at length about an

odyssey of personal discovery where people communicate or express

themselves through the medium of the work they create. Do you see the

web effecting individuals as far as their ability to share their vision

as photographers? Obviously, you have a successful web site for yourself

and your workshops and such. But as another medium of expression; do you

see many photographers using the web in that way?

Freeman: It could be. I have a web

master for my site. You can’t spend all your time in front of a computer

and do workshops and do photography. There’s only so much time. But I

should think there can be a great deal more done by photographers in terms

of web design than has been done up to this point. Really, some

wonderfully creative things.