Chris/Larry: Your images have been on the cover

of more than 200

issues of Sports Illustrated and Time Magazine. How does one begin such an

illustrious career?

Neil: I started taking pictures as a kid around 1954 or 1955, I grew up

on the Lower East Side of Manhattan where I belonged to the Henry Street

Settlement. They had a photo workshop that was run by a wonderful woman

named Nelly Peissachowitz, who really had that ability that good teachers have to

excite young people. Her influence sure worked with me and was a major

factor in

my choice of making a career out of photography.

Chris/Larry: What kind of subjects did you shoot?

Were you always attracted to shooting sports?

Neil: I wasnít immediately attracted to

photographing sports. I was more interested in photographing Navy ships

and Air Force and Navy planes. I used to cut school to photograph aircraft carriers

and battleships coming in and out of the Brooklyn Navy Yard which was

across the East River from where I lived. I wanted to be a Navy pilot when

I grew up. I took the subway and a bus out to Floyd Bennett Field which

was out to the boondocks

of Brooklyn to photograph Navy planes from the highway, as theyíd come in and

out for landings and takeoffs. That was my first real passion. When I got to high school I became the picture editor for

the school newspaper. My staff photographer was Johnny Iacono,

who was also my best friend. Johnny is

now and has been for years a staff photographer at Sports Illustrated. I

started photographing sports more in high school for the school

newspaper. I really enjoyed taking pictures and Ioved seeing my name on

the credit line when they were published. As a kid I didnít have any money and it seemed an

easy way to get into a sporting event was with a credential. The problem

was that I was fifteen years old and I didnít have any credentials.

Chris/Larry: So how did you work around that

little problem?

Neil: I discovered early in the 1958 pro football season that

every Sunday a veteranís hospital would come with three or four bus

loads of army vets, most of whom were in wheel chairs to see the New York

Giants play football at Yankee

Stadium. Since they never had enough people to help wheel them in, I would

wait for the busses to come and volunteer to help, soon becoming a

regular. I was now able to watch every game from along the outfield wall

where the monuments were, we were actually on the field just behind the outfield

end zone. When it got cold late in the season, I would bring a cup of

coffee to the security guards on the sidelines and they would look the

other way when I took out my Yashica Mat, the poor manís Rolliflex, and

shot a few pictures.

There is a picture in my book ďThe Best of LeiferĒ

of Alan Ameche scoring the winning touchdown in what has been

referred to as "the greatest game ever played". It was the

famous sudden death between the Baltimore Colts and the New York

Giants, which coincidentally took place on my 16th birthday, December

28th 1958. When Alan Ameche scored the winning touchdown there were

so many Coltís fans, (mainly drunken Coltís fans) on the field that the

security had their hands full just making sure that they could keep those people

off the field. They werenít worried about someone like me that they had

seen every week. So I ended up exactly ten yards in front of Ameche as he

scored the winning touchdown. He came right at me and I got that picture, which today, is

certainly one of my best-known pictures. I always think that if I had had

any money and any decent equipment, I would never have taken that picture

because, if I would have had a long

lens, a 135mm or a 180mm, I would have tried to fill the frame with Ameche

going in for the winning touchdown. Instead I got the wide shot that

takes in the whole ambiance of Yankee Stadium that afternoon which is so

much better than any picture I would have taken years later when I was an

established pro.

Chris/Larry: So even back then you were able to be

in the right place to capture the moment that defined the game.

Neil: Well, I was lucky. I donít want to sound

like Iím just being modest about it. Most good photographers I know,

sports or any other kind, have pretty healthy egos and Iím certainly no

exception to that. But sports photography is a matter of being in the

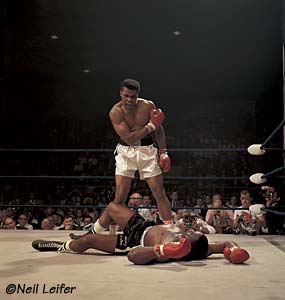

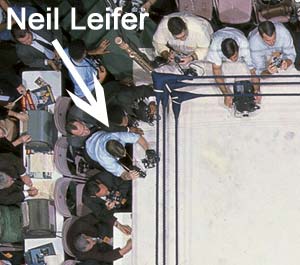

right place. Youíve got to be in the right seat. A great example is to

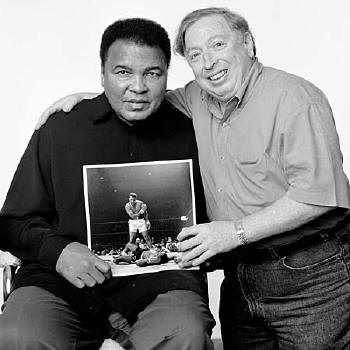

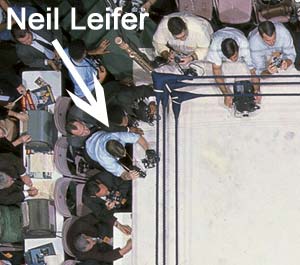

the Liston Ali picture. The photographer you see between Aliís legs is

Herbie Scharfman, the other Sports Illustrated photographer. It

didnít make a difference how good he was that night. He

was obviously in the wrong seat. What the good sports photographer does is when it happens and

youíre in the right place, you donít miss. Whether thatís

instinctual or whether itís just luck, I don't know.

Chris/Larry: A matter of a lot of practice and

training perhaps?

Neil: I just think itís how you view things. If you think of it

as any other kind of photography, basically when the elements are all

there in front of you, how you compose the frame, what lens you chose, how

you chose to shoot it in terms of shutter speed, etc, etc.

Chris/Larry: Throughout your entire career

youíve been able to capture an entire story in a single moment, to portray

the entire event with a single image. How do you tune in to that? Are you

dispassionate when youíre observing the game, are you totally involved?

How do you really know the pulse of the game, or the pulse of the event,

whatever youíre photographing? How do you see the big picture?

Neil: You donít as itís happening. The picture that you shoot in the first quarter

that seems so very significant, quickly becomes meaningless if the game

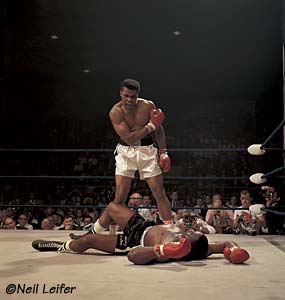

goes another way in the second quarter. My Mohammed Ali Sonny Liston picture

wasnít even published on the cover of the magazine when it happened, so it

wasnít considered such a great picture when I took it. For whatever reason it grew in

popularity as Aliís reputation and stature and legend grew. I think that with sports pictures the objective is pretty

simple. Weíre still journalists, shooting for a newsmagazine like Sports

Illustrated or Time or Newsweek. Youíre there to shoot the star of the

game, in the play that won or lost the game, hopefully in a memorable picture. And you

can't know when that picture is going to happen. Someone once asked me why so much of sports

photography is done with sequence cameras. The inference being that it

lessens the photographerís skill, if you can shoot five frames a second.

Youíre shooting a sequence of the winning touchdown at five frames a

second and one says ďbut how can you miss at five frames a second?Ē

Here's how: Let's say, for example that the ball is on the one foot

line and the fullback leaps up over the line and heís eight feet in the

air, whatever. You get this magnificent moment. That is the picture,

right? Well not necessarily because let's say that

immediately after you snap that picture, assuming youíre shooting one

frame, he fumbles. That picture no longer mattered that was so perfect a

tenth of a second ago. Itís now the ball sailing out of his arms and eight

guys trying to recover it. Five frames a second and youíre still on that

play and you may have the picture that runs as the cover of the magazine.

The opening spread may very well be the picture that happened ten frames

after what at one moment looked like the best picture you could imagine.

Chris/Larry: Just donít run out of film first.

Neil: (laughs) Well thatís an important part of the job for

sure.

Chris/Larry: Can you tell us about any specific

images that influenced you when you were first starting out? Perhaps other

photographers and the things they did that really made an impression that

guided you along the way?

Neil: For starters I was a huge credit

reader. I looked at Life Magazine every week, I looked at Look Magazine

every two weeks, and I began looking at Sports Illustrated when I got keen

on sports photography. All my heroes were the photographers that I hoped

to someday be as good as. Hy Peskin,

Marvin Newman, John Zimmerman, George Silk,

Mark Kaufman. They were really my five heroes. Each one of

them had something that was a bit different. I liked the versatility of a

Mark Kaufman who not only could shoot wonderful action pictures but could

shoot a very sensitive portrait in the studio. I always wanted to know how

to light something as well as Mark did. Mark was one of the original staff

photographers at Sports Illustrated. He also was the first photographer to

do the Life cookbooks. He could do still lifes of food, which to this day

I wouldnít begin to know how to do. I loved the action pictures that Hy

Peskin took. His great boxing pictures in particular still knock me out. And John Zimmerman was someone who could do everything

almost as well as Mark and was even better with action pictures. Marvin Newman was just an all around great sports

photographer. George Silk was more of an artist, more

creative, doing more artsy kind of stuff, but always taking memorable

pictures.

Chris/Larry: Your new book, ďThe Best of LeiferĒ

has a remarkable range of pictures in it. And yet thereís cohesiveness.

Can you describe the common thread, things you absorb from other

photographers. How you interpreted it and how it created in you the

ability to create that body of work?

Neil: Mark Kaufman told me years ago when I was

still a kid, that he thought that being a sports photographer was the best

training ground to do anything in photography. Whether itís a political convention or

election eve, or the Pope coming to America, or war coverage, in terms of

the discipline it was a perfect training ground for everything else. The

techniques that I learned in sports photography were put to terrific use

when I moved over to Time Magazine in 1978. One of the great editors of all times, Ray Cave, had been

executive editor at Sports Illustrated before he became managing editor at

Time Magazine. He offered me the opportunity to move over to Time, which

gave me a whole world to explore rather than just sports, something which I always

wanted to do. Iím very, very proud of my sports pictures. But, you get

pigeon holed. You do something well and suddenly nobody thinks of you as

being able to do anything else. The example Iíve use many times is if an

editor

wanted to shoot Mohammed Ali in black tie against a white background in a

studio, itís get Neil Leifer. But if you want Sidney Poitnier or Denzil Washington, or Will Smith in black tie in a studio,

that editor wouldnít think of assigning me. It's almost as though editors

think I can only speak to and photograph athletes. In fact, either you

know how to shoot a portrait in a studio and make it come alive or you

don't. It isnít like athletes are speaking a different language. Moving to

Time Magazine gave me that opportunity to explore other things. And I used

the very techniques that I had used in sports over and over again. Anybody shooting

sports has to be very adept with long lenses. I probably used a 600 more than any

other lens. So using long lenses to shoot animals for an essay for Time Magazine

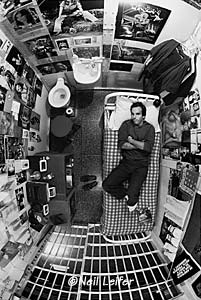

was of course, piece of cake for me. The remote cameras that I used in so many sports

pictures, whether itís under the rail of the Kentucky Derby, over the ring

at a boxing match, or just as an extra camera to get the double play at

second base. I was able to put it to use in many other ways for non-sports

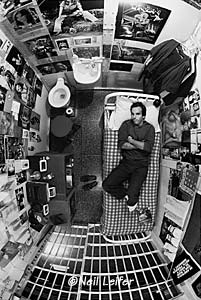

pictures. I mounted one over the cellblock in my prison essay, which was

in fact the cover of the magazine. I put a camera right up over the middle

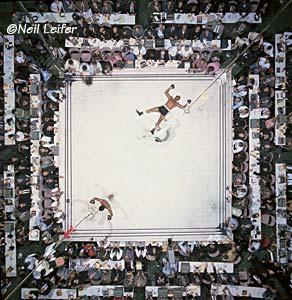

of the cell. Itís no different than my picture of Cleveland Williams and

Mohammed Ali except that this time it was in a prison cell. I hung a

camera from the portal of the bow of the USS Carl Vincent and pointed it

back and shot F14ís coming off the side catapult. No different from any

number of sports remote pictures Iíve done. The skills that you picked up

in sports I just put to use on other assignments.

Chris/Larry: Out of the amazing range of things

youíve shot, you must have your favorites. When you look back, which

pictures are you really proud of?

Neil: The pictures in my book are my

favorite pictures but for different reasons. For example, the picture of Yogi Berra being

picked off second base in the World Series in 1960 happened to be the first full color

page I had

in the magazine. The competition that day was Hy Peskin, Marvin Newman and

John Zimmerman. It was the first time I realized that perhaps I can

compete with these guys. And the picture of YA Title dropping back to pass

was my first Sports

Illustrated cover. So my favorite pictures are not really necessarily my

best ones. Theyíre pictures that bring back memories. Theyíre certain

moments in my career that were very special.

Chris/Larry: It's actually quite a different

question to say what are your favorites verses what do you feel are your

best photographs.

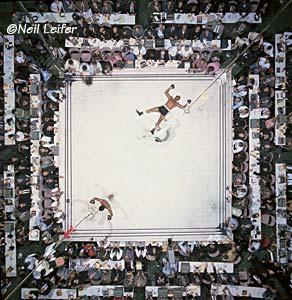

Neil: I know, and my best picture ever, in my opinion, is my Ali Cleveland

Williams picture that I shot from overhead. I donít usually hang my own photos, I

collect other peopleís pictures. But that pictureís been hanging in my

living room as long as I can remember. I have a 40x40 print of it

which is hung in a diamond shape with Williams at the top. That's the guy

thatís on the canvas on his back.

Chris/Larry: Itís remarkably abstract for a sports

picture.

Neil: I

think itís the only picture in my career that thereís nothing I would do

different with it. You look at pictures and think

that you can always improve them no

matter how successful the shoot is. Part of what motivates you to go on to

the next shoot is every once in a while you get a picture, whether it's

the cover of the

magazine or an inside spread, that's as good as you think you

could have made it. And then a week later you see a couple of things that

you could improve slightly. A month later you

might see

a few more things. It doesnít diminish the quality of that picture. It

simply means that there's always room for improvement.

Chris/Larry: Youíre learning for the future?

Neil: Exactly. Itís sort of what motivates you to

go on. If I were to do the Cleveland Williams Ali picture again, I

would do it exactly the same. And more important is that no one will ever do it

better because it canít be done like that anymore. Today the ring is

different and the fighters dress in multi colored outfits like wrestlers.

Back then the champ wore white and the challenger wore black. Today,

when you look down at

the ring from above, you see the Budweiser Beer logo in the center and around

it is the network logo thatís televising the fight. Whether itís Showtime or

HBO, they have their logo two or three times on the canvas. The logo of promoter

of the fight, Don King Presents, is also visible. That's why that picture

couldn't be taken today. So not only did the picture work out better than any Iíve ever

taken, but itís one thatíll never be taken again.

Chris/Larry: Where are you in this picture?

Neil: Iím at 11:00 oíclock, as I remember it. Iím in a blue

shirt leaning on the canvas with a camera in each hand.

Chris/Larry: You were always really creative working with

remote set-ups. How did your editors react to those unique views? Did they encourage you to keep pushing limits and putting cameras

in unique places?

Neil: Yes. They were very excited when it worked. Over the

years, some of my best photos were ones taken by remote. I really followed

in the footsteps of John Zimmerman, who did remote shots better than anyone else. Hy Peskin did a lot of it

also so I wasnít the first person by any

stretch. Photographers have been mounting cameras over boxing rings for years. That picture

of Ali Williams was simply done differently and that was something I

figured out and capitalized on it. I got more fun out of watching

the next fight at the Houston Astrodome when there were eight people

fighting to get the center spot on the overhead grid that I had used. Most

of the time, the ring lights at a fight were about 20 feet up and

supported by poles in each corner of the ring so there was no way to shoot down and get the whole ring in unless you

used a fisheye which distorted the view. You donít get

anybodyís face, just the top of the heads. Something different

than what I wanted. Or you didnít get the full ring in and certainly not

enough of the fans. So most remote pictures of boxing are done with the

camera in the corner of the ring looking out so that hopefully you get one

guy on the canvas and see just a little bit of the face of the person who

scored the knockdown. This was going to be the first fight in the Houston

Astrodome. In order to get

the sight lines clean from the upper decks the lights were going to be 80

feet over the ring. When I realized that, I realized that for the first

time you could put a lens up there, get in the entire ring and get in some

of the seats. But the widest Hasselblad lens at that time was the 50mm. Today I

would have put a 40 or a 30 on it and gotten even more in the picture. The fact was that

for the first time you could put a camera up there and get that kind of an

effect and that I figured out. It immediately struck me that

it would make a good picture. I never anticipating that nice knock out. But

you know, if I hadnít have gotten it at that fight I might have gotten it

at the next fight at the Astrodome.

Chris/Larry: Thereís an early shot of you in the

beginning of the book, youíre basically still a kid, I think it was 1961.

You had the three Nikon cameras around your neck, I noticed that you had a

lot of long lenses on there that did not appear to be Nikon. At the time,

Nikon had a fairly limited repertoire of long lenses. You seemed to be

real creative with having things made to order or adapted to the equipment

you need.

Neil: Sports Illustrated helped me out. At that

point I was already using professional equipment. Iíve got motor driven

Nikons. Nikon did not make a 400. Thatís a 400mm Kilfitt in the picture

and all the other lenses are Nikon. That zoom there was Nikon's first zoom.

I think it was an 80 to 250 or something, I donít remember. And even

compared to the Nikon 300, the Kilfitt lenses were better lenses at the

time. So most pros were using Kilfitt lenses with a Nikon adapter, and it

was very common. In terms of shooting night football and night sports,

probably the best lens thatís ever been made is the 300mm f2.8. A company

called Topcon made a 300mm f2.8 about five years before Nikon did, and for

years Marty Forscher made Topcon to Nikon adapters that

every sports photographer owned. It was a basic lens, the 300mm 2.8.

Chris/Larry: Were these presets?

Neil: They didnít close down on their own. But you

bought a 300mm f2.8 to shoot at 2.8 so you werenít a whole lot concerned.

The Kilfitt lenses were German lenses and were very good. In fact I bought

Mark Kaufmanís 150mm Kilfitt when I began shooting at Sports Illustrated.

Chris/Larry: Of course today people expect cameras

to be auto focus and to have auto exposure.

Neil: They didnít have auto anything then. Nikon didn't even

make remotes for their cameras back then. But Marty Forscher made remotes for them. Al Schneider who

ran the Life studio was also sort of the technical whiz who built things for the great Life Magazine essays. Today you can go out and buy

all sorts of triggering devices that

didnít exist when I was shooting. You either had to have them made or

you didnít have them.

Chris/Larry: Earlier you mentioned how important

luck was as a factor. Itís pretty clear that thereís a lot of preparation

and research and work that goes into being ready when that lucky moment

arrives.

Neil: Exactly, and you canít afford to miss. If I

were going to rate sports photographers it would be by how often they got

lucky and didnít miss. And I think that if Iíve done anything notable in

terms of my memorable sports pictures itís that those were the times I was

absolutely in the right spot at the right time, and I didnít miss.

Chris/Larry: I remember reading, I think it was in

a Time Life photography book, you went to a parkway in New York City to

photograph cars going by at 60 mph as practice for shooting a downhill ski

event. It was obvious that along with having opportunity and luck, you

worked really hard to get your skill up to the point where it was.

Neil: That was a photograph thatís in the book

of Billy Kidd skiing in a downhill race. The camera is a Rube Goldberg

made by Al Schneider. Basically what he created was a portable photo

finish camera. The film goes one way, the subject goes the other way and

instead of a shutter thereís a slit and the subject actually records

itself. I needed to know how fast Billy was going to go and

he said he could pick a spot for me on the hill where heíd be going 60

mph. At that point you want to figure out how to make the film go at the

same speed as the skier so I would get a real image. If the film is going

faster than the skier you get an elongated image, and if the film is going

slower than the skier you get a bulbous sort of squeezed image. Well I knew that the speed limit on this parkway was 60

mph and most people are going at the speed limit, and so I tested at the same

distance, with same lens and the same camera. Thereís a calibration on the

camera and I made notes about what I had done. When I had the setting

that gave me a round tire I knew that the camera was set for 60 mph.

Chris/Larry: And then after you calculated and you

practiced and you worked, you prayed that everything would come together

just right for you.

Neil: I wasnít really worried about my part. Once I knew the equipment was working properly Billy handled the

rest. Donít forget, this isn't like stopping action. I couldnít

miss because as the subject goes by it records itself. So all I needed was

Billy not to fall and to pass the camera at 60 mph, which he promised me

he would do. (laughs) So it was actually pretty easy, all things

considered. I remember even practiced in the winter in New York given the fact that batteries are different in the cold.

Chris/Larry: There are shots though that transpire

in front of you that you only have one chance at. Iím thinking of a

passage in the book where you are actually in competition with Frank

Sinatra at a fight. When youíre in a fast paced situation, like the fight

that weíre referring to, where you and Frank were both shooting it. You

clearly got the pivotal moment. You caught the instant, where he had

some nice overall shots. You both basically had the same opportunity but

you got the shot.

Neil: That isnít quite the way it happened.

This was the first Ali Fraser fight. Because the demand was so high

for credentials and ringside seats, they created a photo pool and Sports

Illustrated was given the pool assignment. I was one photographer and

Tony Triolo was the other. We were the only two pool photographers

shooting ringside. Obviously Life Magazine was going to do

a big piece on the fight in addition to Sports Illustrated, which was

our primary mission. Our pictures were going to both magazines and

both of us would have liked to get the Life Magazine cover. About a

half hour before the fight, an editor from Life Magazine came over and

whispered to me something like, listen, we need one

picture youíve got to be sure to get. Frank Sinatraís going to be

shooting over there in the corner. Make sure to get a picture of him

with his camera. And by the way donít forget to get a picture of

Norman Mailer who was seated in the press section. Now I knew Mailer had been hired by

Life to write the fight, obviously Sinatra didnít have a photo

credential but he certainly knew enough people that they squeezed him

in. And as soon as I was told that, I knew what a smart idea that was

to have Frank Sinatra, who was a serious amateur, shooting ringside.

The truth is that I never viewed him as competition because as soon as

they told me that Sinatra was shooting the fight, I knew the fix was

in that heíd get the cover. I had been asked to photograph

Sinatra, not for a gossip picture but for the publisherís note. They

used a picture of Norman Mailer and a picture of

Frank Sinatra ringside, camera at the ready. As soon as it happened I knew it wasnít going to be

a fair contest for who had the best cover picture. Sinatra got the cover of course,

and Itís OK,

nothing special. I think that if they were looking at the pictures without

knowing who Sinatra was he wouldnít have had a chance. They ran an ad in

the New York Times the day the magazine came out which said In big type ďThe FightĒ.

And then under that it said ďThe Writer - Norman MailerĒ, ďThe

Photographer - Frank SinatraĒ. Clearly theyíd prepared that ad before the

fight. So I never took the competition seriously. The fact is that Sinatra got a

beautiful picture inside because he tilted the camera and created sort of

a ring that was slightly slanted. In my case, if I had sat there playing around in the middle of

the fight they would have fired me because that could have been the moment

that the knockout occurred. The sad part of that fight was that when Joe

Fraser knocked Mohammed Ali down he knocked him down right in front of

Tony Triolo who got the SI cover and

I couldn't have been in a worse seat. So Iím proud of the fact that I got

any picture. I got a picture of Ali and his back with his arms up in the air

and the red tassels on his shoes flying but I didnít get either cover and I donít consider it one of my best days.

Chris/Larry: What are your favorite sports to

shoot? And what are the most difficult sports for you to photograph?

Neil: The most difficult sport for me to photograph was always

baseball, because nothing happens most of

the time. To make good pictures of baseball was always challenging to me.

I mean anyone can take a picture of a collision at home plate if thereís a play at the plate. Or a terrific double play with the shortstop

leaping over the sliding runner. But what do you do when nothing happens,

because so much of the game nothing happens. In football thereís action on

every single play. In Basketball every time you go to the basket thereís a

potential photograph. Baseball was always the most difficult for me to

make exciting pictures. When the action is exciting youíve got to make

sure youíre still awake. But my favorite without question was boxing.

Chris/Larry: And why is that?

Neil: Because you are so close to action. When the boxers are up against the ropes

right in front of your position, youíve actually got to lean back to get them in the

frame, even with a wide-angle lens. Sometimes youíve got to make sure not

to get stepped on. Secondly, thereís a wonderful history. Certainly the

great heavy weight fights of the past influenced my love of the sport. Iím

going back to Joe Louis, Rocky Marciano, Floyd Patterson and young

Cassious

Clay and then Muhammad Ali and George Foreman. Sugar Ray Robinson was

before my time. I photographed him at the end of his career. I just like

the history of boxing and I like the athletes and I like the people. I think

that with a few exceptions, by in large, boxers were the nicest people I

worked with in sports. And I think that most people that cover boxing will

tell you that.

Chris/Larry: I remember reading somewhere that

square was the perfect format to photograph boxing. It seems that overall

in your book a lot of pictures are shot with a square format. Were those

shot with a Hasselblad?

Neil: The square format was only convenient for use with strobes. In the early 1980ís television

barred strobe lights from boxing so by the time Ali was finished we werenít

allowed to use strobes anymore at fights. Iíve used 35mm at all the fights

since then including all the Sugar Ray Leonard and Mike Tyson fights. One

reason we used to use 2 ľ x 2 ľ was the format is wonderful. It

immediately takes away the decision-making whether to turn the camera

horizontal or vertical? The action is going so quick and it takes one

decision out of your hands. You can do that in editing rather

than when shooting. And, with the larger format with strobes, you

were using a slower speed higher quality film. The quality of those photographs

was

just phenomenal. But the main reason one used 2 ľ format in those days was

the synch speed with strobes. I started off with Rolliflexes and then I

moved to Hasselblads later on. The Rolliflex and the Hasselblad both synch

at a 1/500 of a second thereby getting rid of whatever ambient light would

be there so you didnít have a ghost image. Thatís the simple reason.

Chris/Larry: How do you feel about retouching

photographs, digitally or otherwise? Is that a legitimate way to enhance

the way pictures communicate a story?

Neil: It depends on what youíre presenting. If

youíre doing a shot for advertising, sure. Or retouching a scratch. News

photography should certainly not be retouched. When youíre presenting a

news picture itís supposed to be the way it was taken. And if youíre

enhancing things and digitizing things and moving things around, I find

thatís not journalism. I also think that in this book the pictures

should be presented as they were shot. But there are two scratches on my

Ali Liston picture on the cover of the book that have been removed. There

is a scratch in Listonís head and in his hair. And there is a scratch in

the ropes on the left side. Weíve had those taken out ages ago, so that I

have a duplicate transparency that I use for reproduction that doesnít

have those two scratches in it.

Thereís one picture in the book that something was

taken out of it and I was asked how I felt about it. There was a

seagull right over Ed Kochís arm in the picture of Koch. And you

couldnít tell what it was because it looked like a dirt spot.

The publisher came to me and asked if I would mind them taking it out? I looked at it and felt itís not cheating

because the picture youíre looking

at is exactly what I took. Itís the original Kodachrome transparency. But

there was this ugly spot that you couldnít tell

what it was so it was removed.

Chris/Larry: I wanted to touch a bit more on the

later shooting that you did when you were traveling the world and

photographing for Time Magazine and Life Magazine.

Neil: Don't forget I also did a good amount of traveling the world

in my early days with Sports Illustrated.

Chris/Larry: That too, certainly that. But I was

curious about a single quote you have in the book where you say that, ďyou

lose sight of fear when you look through a cameraĒ. Tell us about some of

the interesting situations youíve been in.

Neil: Iíll give you my best story. Thereís a picture in the

book of ice boating and you can see how one runner is

way off the ice. In the 60ís I went out to middle of Wisconsin to do the

ice boating story. Iíd go out every weekend to photograph a former Olympic

sailor named Bud Melges who was sort of my guide and made sure I got

everything I needed. They took me out about a half dozen weekends

in different boats to shoot the ice boating. I was positioned about eight inches off the ice, riding backwards

with no seatbelt. Iím kneeling in this little

cutout like a canoe and riding backwards looking at the skipper. When the wind was right and there were no

snowdrifts they can go as fast as 140 miles an hour. And it's not unusual

for one of the runner blades to be

four feet off the ice. In the dozen times I went out

the conditions were right about three or four times, the other times

we went about 80 miles and hour because there wasnít a really good wind.

But I did do a number of days at 140 miles and hour, loading cameras,

focusing, worrying about the horizon line. Iím not going to suggest that I was never concerned

because every once in a while you grab the side cause you thought the

boat was about to tip over. But most of the time I had so much to think about that I really wasnít afraid.

When I finished the essay the people that Iíd been shooting asked me if the magazine

wouldnít let me come out for a weekend and show them the pictures. They

were going to throw a party and teach me to sail an ice

boat. So I went back and asked my editor if I could bring out a tray of

slides. He said OK as long as I didnít give them any. So I put together a carousel of my selects, my best pictures,

and I flew out without any cameras just to have some fun. This was the

weekend Bud Melges was going to teach me to sail

a boat. So now I'm sitting in the seat you sail from. There was no wind

the weekend I sailed, and since it had snowed all night, there were

snowdrifts on the ice. I donít think we ever got the boat up over 40 or 50

miles and hour tops. Thatís a hell of a difference from 140 miles an hour.

Only now I was controlling the sail. I kept feeling these little pellets

of ice that sort of ting as they come back flying at you from the front

runner blade. I remembered cleaning them off my lens when I was sitting

next to the skipper so that I would get pictures from the skippers point

of view. All of a sudden now

Iím sailing the boat. These things are like bullets but it was nothing

more than an annoyance when I was shooting. Theyíre hitting me in my

cheeks and Iím getting frightened to death. Iíve never been so scared in

my life. And I was probably going 40 miles per hour instead of 140. So I

think the camera, just the idea that you put your mind in another place, not that it gets rid of the fear, but you donít have time to

think about how frightened you are if youíve got all these other things to

think about.

Chris/Larry: You photographed inmates in prison

for the story that was called Inmate Nation. You got some very dramatic

shots, particularly the overhead shots of the cells and such. Was there

any danger there?

Neil: Quite honestly there was nothing to be afraid of there.

Inmates are the most litigious group of people in America and you cannot

run their pictures without releases. The lawyers at Time Magazine were

absolutely insistent that anybody that was going to be in the prison essay

had to sign a release and I had to spend a lot of time talking to them

before shooting. They wanted to know what I was doing and why I want to

take their pictures. Then hopefully I would take what looks like candid

spontaneous pictures. But there was really nothing to be afraid of. You

donít want to spend time in a prison debating the legal system with

inmates. I didnít want to get into their cases, which many of them wanted

to talk about and I would always explain to them that I was doing a photo

essay about how they lived, not debating the merits of the prison system.

Chris/Larry: Tell us about shooting wildlife. You

spent seven weeks in Kenya shooting. That sounds like quite a dream

assignment.

Neil: It was a dream assignment. I think it was the greatest

assignment imaginable. I love animals and it was a thrill to be able to do it the

right way. On the other hand, while seven weeks seem like a long time,

it really isn't nearly enough time. What

youíre competing with are the photographers like the National

Geographic people that spend 18 months in the Serengeti to get their

photo essays. Seven weeks is a very

limited amount of time. For example I saw only one leopard in seven weeks.

So what seems like a lot of time is not really for that type of

assignment. It was very challenging because itís basically hunting with a camera.

Chris/Larry: How long were the assignments

generally? You talk about going to Wisconsin for six weeks.

Neil: They range from five minutes with Ronald Reagan in the

oval office to seven weeks for my animal essay, to a full year of doing the Olympic essay. The

prisons essay was also shot over a 12 month period. The session

with the President of the United States in the oval office is often five

or ten minutes but has to look like youíve been there all day. So it

really varies completely. Another example like when youíre doing movie posters, youíve got people in the middle of doing something thatís a lot

more important than posing for the still photographer. Iíve done what they

call special shoots on movies, for the posters that go outside the theater,

and 20 minutes is a long time to get with Robert Redford or Sean Connery.

The picture thatís on the back cover of the book was

done for Life Magazine, not for the movie company, and it was done at

lunchtime on the Red October set. I have the whole crew of the

submarine including Sean Connery and Alec Baldwin there and I only had 15 minutes. That

was the entire shoot. The Red October set that I shot was not being

used that whole week. They were shooting in the missile bay, which was another set on another

sound stage. It took me two days to light it and figure out what I wanted and

to do my

test shots. When Alec Baldwin and Sean Connery came in I knew exactly

where I wanted them and it was just a matter of putting the real actors where the stand-ins had been.

Chris/Larry: Was there any one thing that you

worried about when going out on a shoot?

Neil: I always worried about getting the exposure right and getting the

picture in focus. Thatís really what I thought most of the time. I

worried about that all the time.

Chris/Larry: Jay Maisel told us exactly the same

thing.

Neil: It was true. You couldnít trust the meter in

the camera. You always had to hand meter and basically you learned from

experience that the best meter was in your head. And a test roll because I

genuinely worried. I was always shooting chrome. The latitude is very very

narrow in terms of getting it to look right in a magazine. And you had to

be nuts not to worry.

Chris/Larry: And thatís exactly what Maisel said.

Everybody worries about that. Which is one of the reasons heís absolutely

gone nuts over photographing with the Nikon D1 and working digitally

because you see immediately what you have.

Neil: I know, I read that in the piece that you

guys did with him.

Chris/Larry: And that really is. Thereís a

wonderful amount of feedback. Of course if youíre in the middle of

photographing a fight or something, where any blow can be the knock down.

Youíre not exactly reviewing your pictures to see if you have them. Never

the less, you can quickly test lighting and test the situation.

Neil: As for the digital stuff, for example. I'm a computer

illiterate. When I went to work

for Frank Deford, editor and chief of The National (the daily sports paper)

we were constantly on very tight deadlines. On the night of the Evander

Holyfield - Buster Douglas rematch our absolute deadline was 11:00 PM.

That was the last minute we could still get a picture to all of our

plants. Everything was being syndicated. But at 11:00 it had to be in.

The fight was supposed to start at 10:30 but theyíre never on time. I had

Ken Regan shooting digital. Weíre talking 10

years ago. I was sitting under the ring

with the guy that had the transmitter and the computer that would edit the

pictures. Ken was shooting digital. The fight began at seven minutes

to 11 and I think it was the second round that Holyfield knocked Buster

Douglas out. By about three minutes to 11 I was viewing three or

four frames of the KO on a screen underneath the ring. I transmitted the

best frame

to New York at 10:59 and it made page one of all the papers.

And that was the very beginning. I was talking to a photographer at the

Daily News yesterday, and theyíre 100% digital now. She hasnít shot a picture

that isnít digital. Thatís all she uses now at the newspaper. I saw digital coming years ago,

like I said, when we did this fight.

You saw the picture of George Bush being sworn in at his 1998 Inaugural?

Well, I was in the fourth position on the mail photo stand. It was AP, UPI and I

think that the Washington Post was next and then Time Magazine. There

were hundreds of newspapers waiting for the picture of the President

being sworn in. I think it was Bob Dougherty shooting with what might have been the

first digital camera I ever saw. He started shooting with the digital

camera when Bush raised his hand and said the first one or two words. He

took the disk out and dropped it to a guy that was right on the stand

below us. They were transmitting it around the world before Bushís hand

went down. Every newsroom used the AP picture, not the before UPI picture, which

shot on film, because the firstest is the bestest. UPI dropped the

roll of film, processed and printed wet in a little portable darkroom they

had underneath but they got clobbered.

Chris/Larry: I understand that now youíre selling

original prints of your work?

Neil: Yes, I have been since 1992.

Chris/Larry: How would someone go about buying one

of your pieces?

Neil: I now have a web site

www.NeilLeifer.com

and we sell prints ordered directly from it. I also have six galleries that represent my work.

They are in New York, Los Angeles, Washington Austin, Palm Beach and Santa

Fe.

Chris/Larry: Tell us about your new love, about

movie making.

Neil: Thereís an old adage about

being on a film set "Either

you fall asleep or fall in love". And I fell in love with the

process and would like to be a successful moviemaker. I went into into

still photography with big dreams. And Iíve been lucky enough for the most

part to have my dreams come true. Iíve had wonderful gallery shows of my

still photographs and

Iím thrilled with the book Iíve got out. Now Iíd love to have somebody

sitting in the back of the Ziegfield Theatre in Manhattan as excited about

one of my movies as they are about the book, or about one of my photo

exhibitions, that would be a thrill to experience.

Chris/Larry: Youíve directed two feature

length films so far, ďYesterdays HeroesĒ, with Ian

McShane and Suzanne Somers and ďTrading HeartsĒ with Raul

Julia and Beverly DiAngelo. Is it a real different way of working to be

making movies instead of doing things yourself?

Neil: It depends. As far as Iím concerned, a

good director is certainly responsible for the entire picture. You hire a

cinematographer, somebody whose vision is the same as yours, who lights

things the way you would light it. In theory, if you look at my Olympic

essay, the athletes around the world, or you look at any number of the

good things Iíve done photographically, Iím directing the photograph. Itís

the same thing. You have to work with people. You have to motivate people

to do their best for you in front of your lens as a photographer. And I

think making movies is just an extension of that. I learned a whole lot

about making movies from being on movie sets and the more I watched, the

more it seemed like a natural extension.

Chris/Larry: Do you see todayís technology making

the movie industry more open to new comers, or do you think the studio

system will continue to dominate as it is today?

Neil: Technology is a separate issue. The studio

system is the system that pays stars 20 million dollars a picture and

distributes films to 3,000 screens on any given weekend. Where as

independent films may open up on half a dozen screens and hope that they

catch fire and get great reviews. Theyíre both interesting areas to work

in. I would love to have somebody give me an 80 million dollar budget to

play with and see what I can do. But on the other hand, Iíd be just

as happy if somebody hired me to direct a film for a million and a half dollar

budget. Both the films I did were small budget films. I think theyíre both

good films but if they werenít, it would not be because we didnít have

enough money to make them well.

Chris/Larry: Do you have any upcoming projects,

anything that youíre currently working on?

Neil: I just produced a documentary for HBO Sports

called ďPicture PerfectĒ which aired the 21st of January. I

worked with another guy named Joe Levine who's a wonderful award-winning

producer. I learned so much. Itís a documentary of the iconic sports

pictures of our times. It was my idea, which I pitched to HBO. And ESPN

just did a documentary based on ďThe Best of LeiferĒ, so Iím learning

about documentaries. I have a documentary idea that

Iím trying to get going. George Plimpton and I want to do one together on

George's magnificent life. So thatís one that Iím playing with. Iíve

also got a feature film script based on a short film about two years ago called ďScouts

HonorĒ which Alec Baldwin and Bill Murray starred in. We went

to a number of festivals with it. The feature will be called ďSearching

for JordanĒ. And what it does is

combine all the things Iíve learned over the years. Obviously I

know a little bit about basketball and shooting sports. But I also spent a

year doing prisons in America. Itís a comedy about two basketball scouts

who are looking for the next Michael Jordan in the prisons in America.

Short timers, guys who are in, not on rape or murder charges, but guys who

go in at 17 and theyíre going to get out at 22 and have nothing to do but

spend eight hours a day playing basketball while they serve their time.

And nobodyís ever heard of them. Theyíre not scouted by the big scouts

obviously, they havenít come from the big universities. Our hero comes

up with the idea that there must be an entire NBA all star team

incarcerated in the prisons of America, and he is going to fine the best

of them. So thatís a project that I'm trying to get going. Ed Pressman, whoís

very successful producer has optioned the project. Itís a long way

from being made into a movie, but weíre getting closer.

Chris/Larry: Whatís the most difficult part about

making a movie?

Neil: The most difficult part is just dealing with

the characters that are Hollywood. Itís challenging and itís fun. The most

difficult part is getting someone to finance your film. Itís so simple,

itís about money. Somebody puts the money up and you can make a film,

period.

Chris/Larry: That would sure bring us a lot of

traffic to our web site (we all laugh). What about the actual distribution?

When you worked for Time Life, what you shot was seen by the world.

Neil: Iím absolutely crazy about my book. I would

do another book with Abbeville Press in seconds because they do such

beautiful books. But I have nothing to do with how they distribute and

market it. I think that if Mr. Paramount or Mr.

Warner Brothers wants to give me 30 million dollars to make a movie, they

can distribute it any way they want. Would I like to see them sell it

properly? Sure. But unless youíre Steven Spielberg or Tom Hanks, you can

get things not only made the way they want it made, but also the

distribution they want. But thatís just dreaming at another level. I would

love to have my book priced lower and available in more book stores with a larger print

run. But thatís what they pay the publisher for.

Chris/Larry: Do you have any parting words for

photographers, any advice you would give to people who are starting out in

photography now?

Neil: Not really, because itís such a different business

today. I do know itís a lot harder today than it was when I started. I

say that because itís become such a popular profession. Itís sort of

become a glamour game in a sense. When I began there were far fewer

photographers and far more places to get published. Today there are more

photographers, far more photographers, coming out of schools with degrees.

Good photographers and far fewer places to work and therefore I think itís

a much tougher business to crack. But having said that, thereís always

going to be another Richard Avadon. Thereíll be another

Annie Leibowitz. Thereíll be another Walter Iooss.

Who knows, there might be another Neil Leifer, you know. I would never

discourage any young person from going into the field but I just think

itís a much tougher nut to crack. A much, much tougher business than it

used to be.

Note from the authors

After we finished the interview, Neil was still talkative so we discussed

the influence he had on my own sports career

Larry: When we were asking you about whether

there were any pictures that influenced you. I just wanted to tell you

that one of your pictures, with the 17mm lens from the corner of the

hockey game between the Bruins and the Rangers was an influence on me.

I went out and bought a 17mm Pentax lens and had it converted to a

Nikon mount by Marty Forscher. And when I was the staff photographer for the Nets, I used it to

experiment in shooting basketball with it. I was definitely influenced by

your career.

Neil: I think thatís the way any

photographer learns. Looking at good pictures and trying to figure out

what the

photographer is doing and how theyíre doing it, and hopefully bringing

your own ideas and your own approach to it and I think that having heroes

is great. I still remember looking at John Zimmermanís pictures. They used

to blow me away, I was such a big fan and Hy Peskinís action pictures. I

always wanted to take pictures as good as Hyís.

Larry: Your boxing pictures are probably

considered the best in the world. I used to look at them and say I wish I

could do that.

Neil: I was there with the greatest athlete

of our time, donít forget. Having Ali as a subject didn't hurt believe

me. No one would remember if

you happen to take the greatest picture of all times of Larry Holmes,

heavy weight champion for a long time, who cares? Who cares? I must have

ten Larry Holmes fights and I canít even remember the last request from

anybody to even use a picture. I mean, when Larry Holmes dies, someone

will call and say, do you have a picture of Larry Holmes? So you know,

nobody cares. And if you have beautiful pictures of Jerry Quary, Floyd

Patterson, nobody calls for them, either. But with Ali, the phone never

stops ringing.

Chris/Larry: Thatís another generation away now

also.

Neil: With sports photography, it sure make a difference if you happen to have

great pictures of an icon, like Michael Jordan, or Ali who's pictures are looked at all

the time. Pictures of them are

sought after all the time.