Chris/Larry: Weíd like

to start at the beginning of your career. You graduated from Syracuse

University in 1968 with a degree in English Literature. But your first job

was as an assistant to Pete Turner. How did a young English lit major

impress a master photographer like Pete Turner?

Eric: Well, I didnít. Just to go back a

bit, my dad was a doctor and he really wanted me to be a doctor. But he

introduced me to an engineer whose hobby was photography, and as soon as I

saw an image come up in the developer I was hooked. I was 12 or 13 at that

time working as a soda jerk at a local pharmacy and saved up all my money

to get darkroom equipment. Once I built the darkroom and started printing, I was on my way.

In my junior year at Syracuse I came down to New York to

see Pete. I had seen his work in magazines, but at the time he was just

heading off on an assignment. The following year I graduated and went back

to New York again. I was just lucky that someone who had been working for

him was leaving at the time, so I got the job, simply on my own desire to

work for him. I had no experience whatsoever but that didnít really count

for me or against me. I guess what did count was my obvious passion to

work with and learn from him.

Chris/Larry: Did you show him your photographs at

that time?

Eric: I did, and I guess I had a pretty

good portfolio for a kid. He liked it, but I think it was my all out

desire, which expressed itself by my coming down to New York to see him,

that really made it happen.

Chris/Larry: Well, you obviously were a quick

learner as well because after about 18 months of assisting Pete you opened

your own studio. You did editorial work for magazines like Life, Travel &

Leisure, Esquire and Time. That's big time stuff for a new guy competing

with really established experienced photographers.

Eric: (laughs) It didn't happen that

quickly. The way that things worked with Pete was that he felt that after

about one to two years you would learn what you were going to learn and it

started to get a little stale for both people. I think he was correct in

that regard that we started to get a little too used to each other. Itís

always good to have someone new.

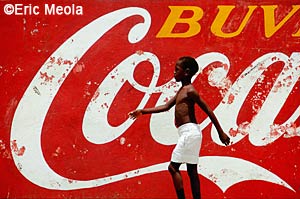

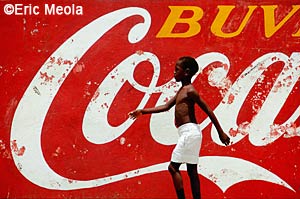

Coca-Cola Kid

So I left and struggled for five or six years with odd

assignments. My first lucky break was when I went to Haiti for Time

Magazine in 1972 and did the Coca-Cola kid shot, which started to put me

on the map. In 1975 the "Nikon Image" book came out. It wasnít an overnight

thing. It took a good five or six years.

Chris/Larry: Can you tell us a little bit about

your vision and what went through your mind when you would get

assignments? Tell us about the process, the way you approached the work.

What kind of approach did you use that really would formulate your work so

that you came up with the images like the Coca-Cola kid?

Eric: I think one of the things that went

through my mind was I should work my butt off night and day. I wouldn't

force the images but it was very important to me that someone was taking a

risk hiring me and that I had to do a good job because I wasnít ever going

to get that opportunity again. It's always important to do your best, but

itís especially important on those early assignments because they can lead

to the breaks that can really help you.

Chris/Larry: Would you ever say to yourself, how

would Pete Turner approach this or how would Jay Maisel approach this?

Eric: I think I would. But I would reject

that, not because they werenít good photographers, but because it's really

a question of what you see with your own eyes. One aspect of Jay's and

Peteís approach I did use was working my butt off.

Photography for me is a passion, not a job. Once

it becomes just a job youíve lost sight of why you originally became a

photographer. It was obvious to me early on that if I took the

attitude of hey, I got the job and that's it, I wouldnít have gotten

anywhere. When I was in Haiti I worked night and day. I didn't stop just

because the sun went down. I would still go out with a tripod or Iíd be up

before the crack of dawn. That's the way I treated all of those

assignments.

Chris/Larry: In the "Nikon Image" book you are

quoted as saying that photography was an all consuming thing in your life,

and if you werenít making money at it, you would still be pursuing it as

intensely. What really helped you to hone your vision and create the great

images that we see today?

Eric: I think probably it was shooting a

lot, experimenting a lot, trying blurs, trying multiple exposures,

shooting at different times of the day. But ultimately it comes back down

to

your eye. I was trying to make images that would stop people as they turn

the page, whether it was through the use of color or graphics or the

subject matter. I was trying to make bold images that made people stop and

ask who took that picture. I was trying to get my name around literally

through the graphic style and use of color, and I guess it worked.

Chris/Larry: It obviously did work. You were able

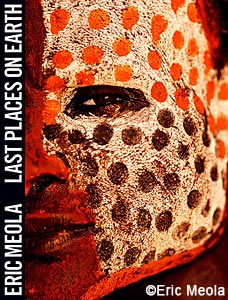

to create some wonderfully strong images. Some of those early photographs

are in your recent book ďLast Places on Earth.Ē It seems that the seeds of

that book started very early in your career. Was that always something

that you had in the back of your mind or did you conceive of it later?

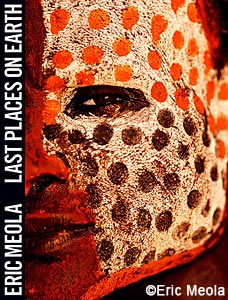

Half Face

Eric: I think I did have it in the back of my

mind; itís just that I didnít realize it. I was always interested in icons

and in the way that one culture had insinuated itself into another

culture. As I went further and further in my career I was dreaming and

thinking about taking an assignment and making it into a book. But the

years kept going by. I would be flying off doing these great advertising

assignments in these exotic places but then I would be back shooting stuff

in the studio. Although I was getting some great assignments, what I had

always wanted to do just kept getting pushed further and further back.

Chris/Larry: I understand Kodak was involved with

the book. How did it all come together?

Eric: Kodak was involved right at the

beginning. I had taken a personal trip to Burma and came back with a lot

of images. Inkjet printers were starting to come into their own at that

time, probably 10 years ago. I made an inkjet portfolio of large prints

and happened to run into a woman from Kodak at an ICP award show. She

asked me what I wanted to shoot which I thought was a very strange

question from the standpoint that people knew what it was that I had been

shooting. We were about to go into this awards show and she said why donít

you come up to Rochester and explain a little more to us what this is all

about. At that point I knew something was up. So a couple of weeks later I

was up in Rochester with all these people and they were firing these

questions at me. Where are the last places on earth? How long would this

project take? What would it cost? About two hours later the meeting ended

and they took me on a tour of Kodak and I flew back. They werenít really

forthcoming with what this was all about.

About a week later my contact at Kodak called to tell me

that I got the project. What do you mean I got the project? She said, you

can go off and photograph whatever you want to photograph. They were not

interested in a book because they had been involved in some publishing

things that hadnít worked out. She explained that they were coming out

with a whole new series of E 100 films and they wanted me to shoot with

that film and let them use the images for advertising. So they left it up

to me as to where I wanted go and what I wanted to shoot. That was the

beginning of the book. I always knew that I wanted to do a book but it was

just that Kodak, though involved, wouldn't be doing the actual publishing

of the book.

Chris/Larry: When you got this dream assignment,

how did you go about selecting the locations that you traveled to?

Hamar Girl

Southern Ethiopia

Eric: I hate to tell you this but it was

completely arbitrary. I didn't want the book to be chapter and verse about

different tribes and A to Z. I really wanted it to be more of a spiritual

journey, which is what it turned out to be. I went to places that I had

always wanted to travel to. Ever since I saw Lawrence of Arabia as a kid I

wanted to go to the Sahara Desert. I had always wanted to go to India. So

literally it was a chance to go wherever I wanted to go to, and that's the

way I did it.

Chris/Larry: When you are photographing people in

a foreign land and dealing with a completely different culture how do you

manage to connect with them so effectively? How do you manage to put the

viewer in touch with your subject and create rapport when the context is

so different?

Eric: I think like most photographers, I

was intimidated by going to some of these exotic places because when you

start to point your camera at someone you feel guilty right away. Then

they shy away or they say no, or they raise their hand. You donít know if

you should switch to a telephoto lens, try to sneak the picture or not

even shoot at all.

Becoming Buddha

When I went to Burma on this personal assignment right

after shooting a big campaign for Johnnie Walker Scotch, I went through a

sort of spiritual transformation. I came across this little boy getting

his head shaved in the ceremony called Becoming Buddha at the Schwe Dagon

Pagoda in downtown Rangoon and it was one of the most incredible things

that I have ever seen in my life. Photographing him, getting that image,

changed me both spiritually and the way I, as a photographer, saw things

visually.

Iím not sure that I can really explain how this all

happened, but from that point on I just was empowered to walk into those

situations and make images. Nothing intimidated me, I didn't try to steal

the images, I didn't try to force my way into these situations. I was very

aware of the personal space of the people that I was photographing, the

culture where I was, and the religion. I respected that, and yet somehow I

had been given this key to walk into these situations and make these

images. It just was all transforming, and it started with being able to

photograph that little boy in Burma.

Chris/Larry: Thatís a remarkable story. It sounds

like your epiphany blessed you with an understanding and a confidence that

attuned you to your subjects.

One of the powerful visual techniques you used in a

number of images in the ďLast Places on EarthĒ was strongly colored

negative space. Many photographers use selective focus to isolate their

subjects, but typically such out of focus backgrounds are muted. You seem

to be drawn to intensely saturated backgrounds. Can you tell us a bit

about that? Do you look for those possibilities as you create images or is

it unconscious?

Eric: It is unconscious. I let the subject

or whatever it is that Iím seeing dictate what happens.

Nomads Shaking Hands

In the pictures in the book the color ranges from the

primary colors that are from the early part of my career to much more

muted tones and the strong use of browns and maroons. I knew I was

changing when I was working on the book and I was allowing that change to

happen. I was shooting in a style that was very different from my early

work.

Fishermen

Inle Lake, Burma

My early work tended to be very carefully thought out

and I would not work around the subject shooting a lot. But when I got to

Burma I couldn't stop shooting. I literally shot 5000 photographs in 4 or

5 days. I was shooting day and night, shooting very rapidly. Not thinking

about anything technical from the standpoint of my early images. In shooting

my early images, I always thought about things that were technical. I

always looked at the exposure. You could ask me 10 years later what

shutter speed I shot a particular image with and I could tell you.

Here I was sort of subliminally aware of the technique.

I was using aperture priority. I was aware of the shutter speeds and the

F-stops in the viewfinder, but not really thinking about them. I mean if

it was five stops under what you could normally shoot at with the F-stop

and shutter speed combination, I didn't care. If I was shooting at a

1/15th

second hand held with a 300mm lens, I didn't care. It really came down

to, hey it might work or it might not but it's interesting. I know there

is not enough light but Iím still going to shoot it. Whereas before I

would have said to myself, I can't shoot in this situation so I wouldnít

try.

Chris/Larry: It sounds like you were becoming

more intuitive and less intellectual about your shooting. Do you think

that great photographs are more likely to come from having an intuitive

connection to the subject?

Eric: I think itís different for different

people, both for the viewers and the photographer. Take Cartier Bresson

who always went for the decisive moment. I think only he would know when

the decisive moment was for him. It could be different for you or for me.

I don't have any regrets about using the intellectual

approach when it worked, but it reached the point where it wasn't working

for me anymore. I was ready to make that change. It didnít matter that 50%

of the images might be blurred or unsharp or whatever because of a lack of

technique, I had to do it. I had to see what it looked like. I had to

shoot whether there was light or whether there wasn't light. It was just

something I was going through.

Chris/Larry: Your wife Joanna McCarthy is an

excellent photographer in her own right. How does being so close to

another photographer influence each of your work?

Eric: Iím glad you brought that up because

Joanna has been an enormous influence, both because she makes good images

and because of her simpler approach to things. I tend to over think

things. She always approaches things with a sense of wonder. Iím always

startled at how differently we see even when we shoot standing next to

each other. Weíll both be pointing our cameras more or less in the same

directions but when we come back and see each otherís images Iíll wonder

where the hell she was shooting to come up with images that I like so

much.

Chris/Larry: If we were to categorize

photographers by their choice of perspective we could say that there are

the telephoto shooters and the wide-angle shooters. Your work is pretty

much telephoto shooting. You take advantage of the way longer lenses

compress space and isolate your subjects. Wide-angle lenses tend to expand

space. Either technique can be wonderful depending on the vision of the

individual. How would you describe Joanna's work?

Eric: I would categorize Joanna in the

middle, meaning she tends to shoot with 50mm lenses a lot. When I came out

of Pete Turnerís studio, one of the things that I was very aware of was

that I had a 20mm mentality. Pete tended, especially at that point in his

life, to shoot with a 20mm lens almost exclusively. Of course there are

always exceptions, but for the period of time I worked with him in 1969

Ė1970, he was using a 20mm lens like it was a glued to his eye.

I came out of there and realized that I was tending to

do the same thing. There was another guy, Tony Edgeworth, who had also

worked for Pete. And he was photographing all these great portrait of the

guards with natural light and telephoto lenses. That was a big influence

as well. I realized that youíve got to see with your own eyes and youíve

got to shoot things the way you see them, so I got away from the 20mm

thing right away.

But Joanna's work has been a huge influence and I think

it's because I can get instant feedback. Iíd see these images and ask,

where did you see that?

Chris/Larry: Can you tell us a little bit about

the circumstances surrounding some of your classic images? Like the

Coca-Cola Kid or your signature image ďThe Promised LandĒ? Are those

things that you set up or are they things you just come upon?

Eric: Coca-Cola kid was not setup at all. I

saw the Coca-Cola sign and I saw people walking by it and I simply set up

my camera across the street. I took a number of images as different people

walking by, then that kid happened to walk by. It was one frame out of a

motorized burst of seven or eight images. None of my travel images are

setups.

Promised Land

Promised Land on the other hand, was a setup. I was

photographing for a moving company in Pasadena California and they had

just built those storage garages. The red paint, the blue sky and the

white stucco of the building instantly looked like a metaphor for our flag

to me. For some reason I got the idea of sticking a white Cadillac in the

doors, sort of a symbol of America biting of more than it can chew. The

next day we saw one on the street and we stopped the guy and asked him if

he could put the car in there, so that was setup.

Chris/Larry: Youíve photographed Bruce

Springsteen for the "Born To Run" album cover. I wonder if he named his

song "Promised Land" after seeing your picture or you named the picture

after hearing his song.

Eric: It's funny because I took that

photograph right around the time of "Darkness on the Edge of Town"í and had

been there in the studio and heard Bruce recording that song. One day

Bruce and I were out at a racetrack and he happened to mention the Chuck

Berry song "Promised Land". He took it from Chuck and Chuck took it from

somewhere, you could go all the way back to the biblical reference, but

yeah I got it from Bruce. (laughs)

Chris/Larry: Tell us little bit about your

relationship with Bruce Springsteen. Youíve shot such classic images of him

that the public almost knows him through your vision.

Born to Run

Bruce Springsteen album cover

Eric: Well, I think the vision really came

with ďBorn to RunĒ. I happened to live around the corner from a place

called Maxís Kansas City in New York where I went to see him and he was

just unbelievable, I mean I was just completely swept away by the music. A

month later I decided to see him at a concert at Central Park. Then I went

to see him at Red Bank, New Jersey and basically bumped into him and

Clarence. And little by little, I started to take pictures. Then one day I

got a call from Bruceís manager Mike Appel saying we would like you to

take some pictures for his new album called "Born to Run". We only shot in

the studio for a couple of hours, but came up with an iconic image. Bruce

is a great guy. Heís the most down to earth person you ever met, easy to

know, not at all a rock star kind of a person. It goes back to following

your instincts. I think that happens a lot with photographers who are

passionate about the work.

Chris/Larry: He seems to be someone whose passion

for music is very analogous to your passion for photography. You clearly

appreciate that level of engagement.

Eric: That's an important point. At that

time Bruce was evolving musically. I think he wasn't really comfortable

with his own persona or look, but it all came together on that album.

Before that he wasn't quite sure how to act around the camera but from

that point on he was equally interested in photography and being

photographed.

Chris/Larry: When did you begin to shoot

digitally?

Eric: I started shooting digitally about 3

years ago. My first digital camera was the Canon 1DS. Until recently I

didnít think that the quality was there. It's really been the evolution of

three things -- the computers, the software and the cameras -- that allowed me

to finally move into it.

The workflow was the bear of the transition, not the

cameras or the other technology. It also brought in a huge change in how

you could catalog your work. Iíve been scanning, believe it or not, since

the late 80's because I realized everything was going to transition to

electronic submission and that kind of thing. But back then computers

werenít powerful enough, RAM wasnít available, and Photoshop wasnít even

able to handle RAW files.

Chris/Larry: Could you describe your typical

workflow from shooting to finished images?

Eric: Well, Iím basically a Photoshop kind

of guy. I shoot with the Canon 1DS Mark II now. I always shoot in RAW. I

sometimes carry a laptop around but I don't use digital wallets. I had

some compact flash card problems in the beginning, every once in a while

loosing an image or two, but I think thatís all smoothed out. I do preview

a lot on the back of the camera and I edit on the back of the camera to

some degree but I tend to leave most of the editing until later on. Up

until recently Iíve been using Photoshop CS2. As soon as I can get my

hands on Aperture, Iím pretty sure thatís the way I am going to edit in

the future. Iíve seen demos of it and it just seems like the way to go in

terms of its speed and the way itís been thought out.

Chris/Larry: Has shooting digitally changed your

vision at all or do you see it as a different tool to accomplish what you

would have done yourself anyway?

Eric: I don't know that itís changed my

vision. I do think itís an incredible tool. I shoot a tremendous amount

more but itís not because there is no film or processing costs or not

having to wait for the film to be processed. I can experiment a lot more

with digital. Things that I might not normally photograph or think might

not make a good picture I shoot anyway just to see what it looks like. I

can always edit it or just erase the images. In that sense it has changed

the way I shoot.

Chris/Larry: Do you shoot ever film anymore?

Eric: No.

Chris/Larry: Early in your career you shot images

as the start of an enhancement process, using duping or other techniques

to intensify color or the graphic quality of the image.

Refinery

Galveston Texas

In camera multiple exposure

Eric: Yes, but I don't feel that way at all

now. I will say this however -- if you shoot digitally, at some point, you

or someone that you hire will need to process your images. In my case itís

me. I don't know of anyone who simply opens the image and hits "save". No

matter how good the profiles are or how good camera is, part of the

control is to be able to adjust the contrast, the brightness, or

saturation. But I try to do it minimally. I try to process the image to

really capture what I saw with my mind's eye. Now that's obviously not

always going to agree with what was really out there, but then, what was

really out there?

Chris/Larry: Was that what you were doing with

film 30 years ago?

Eric: Well, no, 30 years ago I was

intellectualizing a lot more, thinking about multiple exposing or

radically altering with duping later to change the image. Now I tend to do

what I see in my mindís eye but itís a lot more realistic. If you were

somehow able to show the original subject next to my finished images 30

years ago, compared to the way Iím shooting now most people would see my

current work as more natural and normal.

Chris/Larry: You have been working with Photoshop

since the very beginning, scanning film before you began shooting digitally.

Do you still do all your own Photoshop work today?

Eric: Yes that's correct. Iíve been using

Photoshop since the early 90's and I am very cognizant of all the

different ways of altering an image. I use Photoshop as a tool to

work with my images, as opposed to altering them. There is a

tendency is to alter images a lot more than they have been altered in the

past and I don't think that's necessarily a good thing. It all comes down

to who are we as photographers and what are we are trying to do with our

images. If youíre an art photographer, and those things are appropriate to

what youíre doing, fine. But a photojournalist making a gray day into a

bright sunny day? Iím very careful about how I process my images both from

a technical standpoint and with an understanding of what the image looked

like originally.

Chris/Larry: You were a success for many years in

the advertising field but the whole business of photography is changing.

What do you see as the good and bad from those changes?

Chopper

Sikorsky Helicopter photographed over Dallas

Eric: Well I think one of the biggest

changes is that a lot of good new photographers arenít getting an

opportunity to make a living. Advertising was great for me. I made money

at it. I made a reputation at it. But the other side of it is that I was

spending so much time doing things that are not related to photography.

98% of my time was spent bidding, putting the job together, and dealing

with all the personalities to make everyone happy. In the end you can't

make everyone happy and I didnít become a photographer to spend only 2% of

my time making images.

Fire

Eater This was shot for Almay

Cosmetics in 1981. Originally they wanted me to shoot straight down

into a tank of water and have the woman's face submerged, popping up.

I had to go through hoops to explain why she'd reflexively be

clenching her face and have trouble breathing. I finally I convinced

them to let me shoot her in a much more tranquil way, floating in the

tank of water. I used a large bank of gels to reflect into the water

for the background, then lit her face with a blue gel and spot-lit her

lips; we cast more than 200 models for the "perfect lips." Then the

agency told me I had chosen the model they always worked with! We

built a large plexi tank and when it was filled it began to bow to

point where it nearly came apart, with live wires running all across

the floor. We had dozens of polecats spring loaded, pushing against

the plexi walls from the outside. The heat had gone off in the studio

that day and the model was freezing. Everything that could go wrong

did, but in the end we got a great shot.

Fire

Eater This was shot for Almay

Cosmetics in 1981. Originally they wanted me to shoot straight down

into a tank of water and have the woman's face submerged, popping up.

I had to go through hoops to explain why she'd reflexively be

clenching her face and have trouble breathing. I finally I convinced

them to let me shoot her in a much more tranquil way, floating in the

tank of water. I used a large bank of gels to reflect into the water

for the background, then lit her face with a blue gel and spot-lit her

lips; we cast more than 200 models for the "perfect lips." Then the

agency told me I had chosen the model they always worked with! We

built a large plexi tank and when it was filled it began to bow to

point where it nearly came apart, with live wires running all across

the floor. We had dozens of polecats spring loaded, pushing against

the plexi walls from the outside. The heat had gone off in the studio

that day and the model was freezing. Everything that could go wrong

did, but in the end we got a great shot.