Kenneth Huff uses software made for animation and movie special

effects to create virtual three-dimensional objects. He arranges them in

scenes, colors them, then captures them with a virtual camera. He uses

no physical objects to create his intricate organic-looking images.

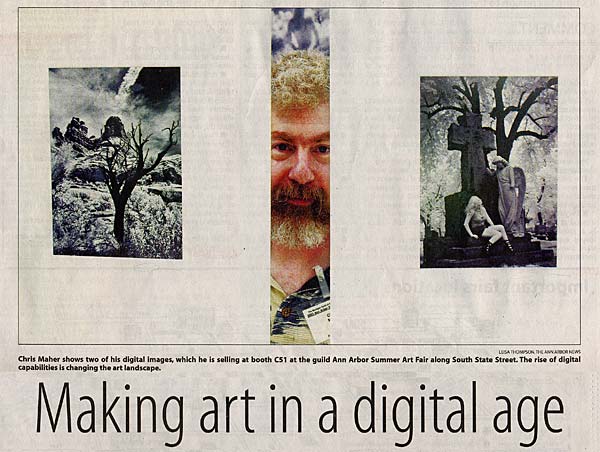

Chris Maher uses a digital camera, altered to be sensitive to

infrared waves, to capture an ethereal glow from living things. "I can

show things to people in a way they've never seen before," he says.

The two men showing in the Ann Arbor Art Fairs believe they're

exploring a new, pixelated frontier, where artists can spawn ideas and

turn a two-dimensional drawing into a sculpture more easily than ever

before.

Fairs grapple with digital

Art fairs lean toward upholding traditions of hand craftsmanship.

They don't aim to deliver the shock of the new, the way some galleries

do. But art fairs are having to contend with the digital age.

"The computer is taking over the world," so it's bound to have an

impact on art, says Tim Osius, program director of the Summer Art Fair.

Jurors for each of the four Ann Arbor art fairs find themselves

deciding the merits of works in a new category called digital art -

still sparsely settled turf. And since artists are experimenters by

nature, fair organizers and artists in many traditional categories like

photography, clay and painting are feeling their way through a thicket

of issues raised by computer technology.

Among them: If an artist in clay uses design software or produces

objects with a computerized kiln, is the work original and handcrafted,

the heart's desire of art fairs? What about the work of photographers

who play with color using software, or love the effects they get with

high-quality commercial inkjet printers? Or the creations of woodworkers

who explore rapid prototyping technology?

Some say the debate among artists centers on a larger question: Is

art considered art because the final product engages the viewer, or does

it matter how it was made?

A growing number of artists in traditional media find computers are

great tools, says Huff, the sole digital artist in this year's Street

Art Fair.

Yet exhibitors in categories like leather, wood and clay that are

traditionally hands-on sometimes run into red flags from jurors and the

public, he says. "There's that hint of mass production there."

Huff, who won a Street Art Fair award this year, is an enthusiastic

proponent of digital techniques who offers a primer on them at his Web

site (www.itgoesboing.com).

"Anything that allows an artist to explore more ideas is a good

thing," he says. "Anything can be used in good or bad ways."

Defining a new category

This year, fairgoers will find seven artists showing in the digital

arts category sprinkled through the fairs. Many more showing in

traditional categories use computer technology, especially in

photography.

The South University Art Fair has one digital artist this year. It

plans to formulate a policy about the use of computer technology. The

State Street Area Art Fair accepted three artists out of 25 applying in

its digital art category.

The Michigan Guild of Artists and Artisans, which runs the Summer Art

Fair, has set guidelines for artists showing in its digital category

after much discussion last year. Artists who use digital images of

pre-existing original paintings, photographs, drawings and other works

don't belong in the category, although they may meet criteria for other

media.

The Street Art Fair doesn't confine digital to two-dimensional work.

The fair, which has had the category for eight or nine years, has seen a

rise in applications, says director Shary Brown.

In other media, digital is touchy

As for artists showing in other categories, the Ann Arbor fairs have

proved more easy-going about digital innovations than some other fairs.

One prestigious Florida fair briefly banned digital work before revising

its policies. Photographer Maher, the Summer Art Fair's lone digital

artist this year, decries the "not allowed" approach.

"It encourages people to hide their use of computers. It's

shortsighted. Artists won't stop using it," he says.

The Street Art Fair relies on its required artist statements, posted

in each booth. "We've chosen to go the information route in encouraging

audience members to ask (about the artist's process)," says Brown.

Artists who are open about using computers can't count on a receptive

public. "When people find out an artist is using (computer technology),

in many people's minds it cheapens it," says Maher.

Huff can't stand the term "computer generated" to describe what he

and other artists produce using computer technology: "It makes it sound

like the computer is doing the art instead of the artist," he says.

"That's completely backwards."

Huff says people entering his booth usually get over their initial

skepticism and engage with the images.

"I've seen mind-sets being changed," he says.